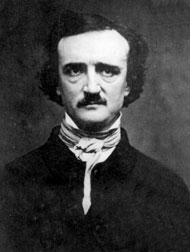

"We know that the British bear us little but ill will… In letters as in Government, we require a Declaration of Independence— a better thing still would be a Declaration of War". - Edgar Poe

_______

The Purloined Life Of Edgar Allan Poe

by Jeffrey Steinberg

This account is based on a lecture delivered in Detroit, Michigan in mid-September 2003, to a group of LaRouche Youth Movement members who have launched a research project to revive the life and works of Edgar Allan Poe.

A great deal of what people think they know about Edgar Allan Poe, is wrong. Furthermore, there is not that much known about him—other than that people have read at least one of his short stories, or poems; and it's common even today, that in English literature classes in high school—maybe upper levels of elementary school—you're told about Poe. And if you ever got to the point of being told something about Poe as an actual personality, you have probably heard some summary distillation of the slanders about him: He died as a drunk; he was crazy; he was one of these people who demonstrate that genius and creativity always have a dark side, and the dark side is that most really creative geniuses are insane, and usually something bad comes of them, because the very thing that gives them the talent to be creative is what ultimately destroys them.

And this lie is the flip-side of the argument that most people don't have the "innate talent" to be able to think; most people are supposed to accept the fact that their lives are going to be routine, drab, and ultimately insignificant in the long wave of things; and when there are people who are creative, we always think of their creativity as occurring in an attic or a basement, or in long walks alone in the woods; and creativity is, also, not a social process, but something that happens in the minds of these randomly-born madmen or madwomen.

Especially in the fields of literature and music, it's almost as if there's a warning out there that bad things happen if you try to be creative. And if you try to really excel at being creative, really terrible things are going to happen to you. Poe is one of the people of whom, they use a falsification of his life to make that false point.

Our Mission As Truth-Seekers

Now, since our job, as a political movement, is that of being the truth-seekers—and in that sense, the moral conscience of America and the world—it's not just an issue of abstract interest that we ought to get to the bottom of the case of Edgar Allan Poe.

In our case in particular, there are some very important parts of the Poe legacy that urgently need to be revived today. On an even more personal level, the last time that we published anything really substantive about Edgar Allan Poe—apart from some papers and presentations that Lyndon LaRouche has given in which he's made reference to Poe and to some of his writings—was in June of 1981, in the issue of The Campaigner which was appropriately headlined "Edgar Allan Poe: The Lost Soul of America." The author of this article, Allen Salisbury, died a number of years ago, in his early 40s, of cancer; basically, the work on Poe has really been set aside and remains unfinished. So there's a sense that the LaRouche movement has a kind of debt of gratitude to Allen that needs to be filled, by completing the work on Poe. And as I get into the discussion about what I've done so far to get the ball rolling, you'll get an idea, I think, of why this is something extremely timely right now.

What I really want to talk about, then, is a very preliminary work-in-progress, that hopefully will inspire a number of people in this room to join with me in really pursuing this puzzle; and, in effect, "cracking the case" of Edgar Allan Poe.

There's one very good source of information about Poe, which necessarily has to be the starting-point for where we go. That starting-point is Poe's own mind, as he himself presents it, in a number of writings that were published during his lifetime, and at a time when he was in a position to review the galleys before they went to press. In some cases, the articles and poems that he wrote were published in magazines that he himself edited. The reason that's important, is that when Poe died—as you can see, at a very young age, 40 years old; and there's ample evidence that he was assassinated—what happened immediately is that his aunt, who was also his mother-in-law, and who lived with him for most of his adult life, was in desperate straits of poverty when Poe died. One of Poe's leading enemies, a man named Griswold, went to her and offered her what, by her standards, was a pretty big sum of money, to turn over all of Poe's personal effects: all of his letters; all of the original manuscripts of his writings; and all sorts of other things. Because Griswold said that he wanted to come out in print with a definitive biography, and that this would be part of the collected works of Edgar Allan Poe. And in fact, a few years later, he came out with a biography that was a complete and total slander.

Many years later, people came forward and admitted that they knew that a number of letters that were attributed to Poe, had actually been written and forged by Griswold, to convey the idea that he was an alcoholic; that he was a drug addict; that he was, basically, a pathetic, psychotic figure towards the end of his life.

And so therefore, even Poe's own letters, which were first published under Griswold's supervision, are not reliable. So as I say, the starting point with Poe, has to be to look at his own mind, and to make certain judgments on the basis of that; and then, it gives you at least a framework for saying what's true about the fragments of his life which are available, and what necessarily has to be wrong, because it completely contradicts what we know about him by knowing how his mind works.

Thorough Is Not Necessarily Correct

There is one particular work that I'm going to rely on for the purpose of exploring Poe's mind; but, what I really want people to do is jump in; you could pick virtually anything by Poe and read it, and come away with the same sense of how his mind works. I think it's a very good idea, particularly for anybody who is going to join me in working on this project, to do exactly that. I want to talk briefly about one of Poe's short stories, “The Purloined Letter.” I'm not going to read it; it's quite short, and I'm going to give you the gist of it, and then zero in on a few things that will give you an idea of how the guy's mind worked.

Poe invented this character named C. August Dupin, who is a French private investigator. A number of stories by Poe center around this character Dupin—"The Murders in the Rue Morgue" and "The Purloined Letter" are probably the most famous. In this story, you've got, basically, three characters on stage. You've got the narrator, who's a friend of Dupin. You've got Dupin; and you've got the prefect of the Paris police—the chief of police of Paris. The narrator and Dupin are sitting around late at night at Dupin's apartment in Paris; and there's a knock at the door, and the prefect of police comes in.

He says, basically, "Dupin, we need your help. We have a case that's really simple, but it's got us completely stumped."

The story is, that there is a minister of the French government who has stolen a very incriminating letter, that represents blackmail against another figure in the government. So the police have been asked to get the letter back, and to end this terrible political crisis. The police know, definitely, that this particular minister stole the letter; because there were eyewitnesses to the fact, who were too embarrassed to say anything. They also know that the minister keeps the letter very close and easily accessible; because the blackmail may have to be sprung on a moment's notice. Therefore, he can't have hidden it away in some hard-to-get-to place; he doesn't bury it underneath a tree, or out at a country estate, or something like that. It's in his own apartment.

The minister is away from his apartment very, very frequently; to the point that the police have been able to go into his apartment dozens of times; and they've carried out thorough searches. They've looked in all of the obvious places that somebody would hide something like this. They've used microscopes to check for hidden planks in the floor. They've gone into every nook and cranny in the apartment; they've checked every table and chair leg. They've looked for false bottoms in desk drawers and things like that. And they've come up with zero, empty-handed.

Now, unfortunately, they have no choice but to go, embarrassingly, to inspector Dupin, to ask for his help. And what happens is absolutely amazing. Dupin says, "Well, if you want my help, there will have to be a substantial reward. This is a big deal, a government scandal; there's a lot at stake here." The inspectors say, "Well, I'm sure we could oblige you with some kind of financial remuneration." And Dupin says, "I want 50,000 French francs. Will you promise me right now, that you will give me 50,000 French francs if I can produce the letter?" The chief of police hems and haws, and eventually says, "Yes, it's a deal." The inspector leaves, and returns several days later to Dupin's flat. Upon the inspector's arrival, Dupin opens up a desk drawer, takes out an envelope, and hands it to him; it's the letter. It's the document that the police have been desperate to find.

The prefect is so shocked, and at the same time so relieved that the case is now solved, that he immediately writes out a check for the 50,000 francs and goes running out. And the narrator—the third person on the scene—is sitting there completely dumbfounded. And he asks, “What just happened?” So Dupin explains to him: “Well, I happened to know something about this minister. He's a mathematician and a poet.”

Underlying Axioms

He says that if the minister were only a mathematician, the police would have solved this case on their own. A mathematician thinks in formal, logical terms, and operates off a set of underlying axiomatic assumptions, that may work in the narrow domain of formal mathematics, but do not work in other areas, such as morals. The formal axiomatic assumptions of mathematics don't work in morality.

But Dupin knows that this guy's also a poet. And so his mind works in a way that's not confined by those kinds of underlying formal, fixed axiomatic assumptions. And he goes on at some length, explaining: I know how these police operate. And they're very thorough; and if they were up against the mind of a mathematician, thoroughness would have caught him every time, because a mathematician is totally predictable. But a poet, on the other hand, has a concept of metaphor, and irony, and therefore is able to think in a way that's not defined by the same strict set of underlying axiomatic assumptions. Therefore, I have to think about how to catch someone whom I know is both a mathematician and a poet. And I knew that this had to be the case: that he needed to have the letter in easy access to where he was; so I knew it was in the apartment.

But I also knew that he hadn't hidden it in one of these super-secret places that the police would find. In fact, I surmised that he was playing with the police all along. Because by being out of his apartment at great length, throughout many, many days, he knew that the police were going to break into his apartment, and were going to thoroughly search it, in the predictable ways that the police, using the same kinds of mathematical underlying axiomatic assumptions, would do the search.

He says, "I knew that; and therefore, I knew that the letter had to be hidden in some place that was in such plain sight, and so obvious, that the police would never think to look there, because they couldn't imagine somebody would 'play us like that'; that somebody would hide something in plain view."

So he says: What I did, was I came up with a very good pretext to go visit the minister. And he immediately invited me in; we got into a long talk about something we were mutually interested in; and all the while, I was looking around, to figure out where it was. And there, above his desk, was a letter box. And right in the middle of the letter box, there was a letter. And I could surmise by the paper, that this was, possibly, the stolen letter. And I noticed that the letter was badly crumpled up, and dirty, and ripped up around the edges. This wasn't something that would naturally happen. So I surmised that he probably had done that to make this appear to be something completely irrelevant and inconspicuous. And I managed actually to take notice, that the letter had been folded inside-out; as if you had a piece of paper that you folded one say; and then you reversed it and folded it the other way; and I noticed that the crease was doubled up.

And Dupin saw that there was a seal on it, that was somewhat similar to a ministerial seal. And so, he just left. And several days later, he came back for another visit; in the meantime, he had prepared a duplicate piece of paper; and had sealed it, and reversed the fold, and made it dirty in a similar way to the letter that he wanted. And at a certain point in the visit, there were loud shouts and screams outside the window. The minister went running over to the window to see what was going on. At that moment, Inspector Dupin just made the switch. The guy looked out the window; it turned out that it was some psychotic who was threatening somebody with a shotgun, and actually fired a shot. And Dupin says that, of course, the shots were blank; this was somebody that he had actually hired to make the incident, to give him enough time to switch the letters.

Dupin even says, that he didn't want just to steal it; because the guy's livelihood and future career depended on having that letter. And if he happened to notice that Dupin had swiped it, without having a replacement, there is no telling what the minister might have done. He might have tried to kill Dupin. So I wanted to make my escape safely, Dupin explained.

On the other hand, I left something in the piece of paper that I left, so that when he opened it up, he would have some clues, to be able to figure out it was I. But by that time, the game would be up. The letter would be returned. And everything would be corrected.

Just to read you a couple of paragraphs to make sure that you get an idea that this is really how Poe's mind is working—I'm not attributing things to him that he didn't really say:

Dupin: The Prefect and his cohorts fail so frequently, first, by default of this identification, and secondly, by ill-admeasurement, or rather through non-admeasurement, of the intellect with which they are engaged. [In other words, they don't try to think about the mind of the criminal that they're trying to catch.] They consider only their own ideas of ingenuity; and, in searching for any thing hidden, advert only to the mode in which they would have hidden it. They are right in this much—that their own ingenuity is a faithful representation of that of the mass; but when the cunning of the individual felon is diverse in character from their own, the felon foils them, of course. This always happens when it is above their own, and very usually when it is below. They have no variation of principle in their investigations; at best, when urged by some unusual emergency—by some extraordinary reward—they extend or exaggerate their old modes of practice, without touching their principles. What, for example, in this case of D—, has been done to vary the principle of action? What is all this boring, and probing, and sounding, and scrutinizing with the microscope, and dividing the surface of the building into registered square inches—what is it all, but an exaggeration of the application of the one principle or set of principles of search, which are based upon the one set of notions regarding human ingenuity, to which the Prefect, in the long repeat of his duty, has been accustomed? Do you not see he has taken it for granted that all men proceed to conceal a letter, not exactly in a gimlet-hole or in a chair-leg, but, at least, in some out-of-the-way hole or corner suggested by the same tenor of thought which would urge a man to secrete a letter in a gimlet-hole bored in a chair-leg? And do you not see also, that such recherchés nooks for concealment are adapted only for ordinary occasions, and would be adopted only by ordinary intellects; for, in all cases of concealment, a disposal of the article concealed—a disposal of it in this recherché manner,—is, in the very first instance, presumable and presumed; and thus its discovery depends, not at all upon the acumen, but altogether upon the mere care, patience, and determination of the seekers....

Algebra and Poetry

So he goes on for a while. You get the idea: There are underlying, axiomatic, formal-logical assumptions that the police make, that work if you are dealing with another mind that's similarly engaged in formal logic, and has no real creativity. Then he goes on to the question of algebra and poetry.

Dupin: I dispute the availability, and thus the value, of that reason which is cultivated in any especial form other than the abstractly logical [in other words, the process of human cognition is what counts]. I dispute in particular, the reason educed by mathematical study. The mathematics are the science of form and quantity; mathematical reasoning is merely logic applied to observation upon form and quantity. The great error lies in supposing that even the truths of what is called pure algebra are abstract or general truths. And this error is so egregious that I am confounded at the universality with which it has been received. Mathematical axioms are not axioms of general truth. What is true of relation—of form and quantity—is often grossly false in regard to morals, for example. In this latter science it is very usually untrue that the aggregated parts are equal to the whole. In chemistry also the axiom fails. In the consideration of motive it fails; for two motives, each of a given value, have not, necessarily, a value when united, equal to the sum of their values apart.

A Platonic Republican Thinker

And he goes on along these lines. And this is a short story; and he's getting into a lesson in epistemology, in the method of how you think.

So, this is really a fun short story which is, I think, exemplary of Poe's mind. This tells you a number of things that are quite interesting. Number one: Obviously, Dupin is part of an interesting kind of intelligence network that knows what is going on in Paris. Number two: He not only was able to diagnose the mind of the minister who stole the letter; but it was also a piece of cake to conclude that sooner or later, the prefect of police was going to come knocking on his door; because he knew that the police couldn't solve this problem.

So we know something about Poe. The guy knows how to think. He's an intellectual of the sort that was versed in Plato; that understood all of the key scientific issues of the day; probably was familiar with Gauss; he certainly was familiar with Schiller, because there are reviews that he had written of Thomas Carlisle's biography of Schiller, that he had made comments on in one of his magazines.

But the problem is, that even just by reading this one story—and I can tell you, that you can pick at random anything by Poe, that's certifiably something that he wrote, whether it's a poem, or a book review, or a short story, or novel—and you'll come away with the same sense of the guy's life. He didn't have"“good days and bad days" in terms of his writing. He didn't have profound second thoughts. He was a thorough-going, studied, educated Platonic republican thinker.

Knowing that, you have got to start from the presumption that most of what's official about Poe's life—all of the biographies, that all followed off Griswold's—were complete fabrications.

He died under very mysterious circumstances in 1849, at the age of 40. In 1885—that's 36 years after his death—the doctor who attended him on his deathbed wrote a book, called Edgar Allan Poe: Life, Character, and the Dying Declarations of the Poet. An official account of his death by his attending physician, John J. Moran, M.D.. In this book, Moran says, basically, everything that's been said about Poe's death is a lie. Every single thing. And he says furthermore, I've been in contact with members of his family and others; and most everything about his life, at least the conclusions that are drawn in a lot of the descriptions of his life, are also false.

So let's just start from the presumption that we're going to investigate Poe's life, using the exact same method that Dupin used in "The Purloined Letter." I'll tell you what I've done so far—because the problem that comes up, is: How do you deal with someone who, you at least hypothesize, was part of the American republican intellectual circles that were involved in the struggle both to defend the American republic during a period of great danger to its survival, and who was also committed to the idea of spreading these republican ideas around the world?

Now, there are a few important clues, in certain aspects of Poe's life, that are so well documented that you can't really deny them. Like the fact that he was born; and he had parents; and there were known addresses where he lived; he had jobs, and people knew him; so there are some things that are known. Then you get into really murky areas, where there are some things that are said to have happened, according to accounts of people; but which, others say, are completely untrue. How do we start to put together a clearer picture? How do we develop a notion of what's true from what's false about Poe, starting from the fact that the only thing we're really certain about, is we know how his mind worked; and therefore, we know him pretty well?

Poe Family and Lafayette

Poe was born in 1809. His parents were actors who travelled around the United States doing performances—everything from Shakespeare to Greek Classics, to much more light, contemporary plays. Both his parents died, within a few months of one another, in 1811, when he was two years old. He had a younger sister and an older brother, and the three children were split up. The brother went to live with grandparents; the younger sister was adopted by a wealthy family in Richmond; and Poe was also adopted by a wealthy merchant in Richmond, a man named Allan.

Now, what's interesting is that Poe's grandfather, David Poe, was a rather important figure in the American Revolution. He was the deputy assistant quartermaster general of the Continental Army, and was assigned to the area around Baltimore, Maryland. He'd been a lawyer there, and the grandfather had actually contributed a fairly sizable amount of his own money to outfit local branches of the Continental Army. And, in fact, the commander of the Continental Army in that area at the time, was the Marquis de Lafayette, who was a leading member of Benjamin Franklin's international youth movement.

Lafayette was born in 1757, and he lived until 1834. Now, in 1776, when he's 19 years old, he decides that he's going to leave France and to come to North America, and he's going to ask for a commission in the Continental Army. As a young man, he's been put through military training in France, and through sort of an elaborate process, he actually manages to leave France. The government was not exactly favorable to the idea of young princes coming over and fighting in North America, but he manages to get over here. And, at the ripe old age of—just before his 20th birthday—he's commissioned as a Major General in the Continental Army. So, you really do get the idea that we're talking here, about a youth movement, that was instrumental in fighting the Revolution.

So, Lafayette has a particular debt of gratitude to Edgar Allan Poe's grandfather, because the grandfather puts up his own money to equip the Continental Army units that are commanded by Lafayette. And, in fact, the grandmother spends all of her time, basically sewing uniforms for the Continental Army. She personally sews 500 uniforms for part of Lafayette's military unit.

Please go to archive.schillerinstitute to continue reading.

________

The following is part 4 of a new series 'Edgar Poe as Cultural Warrior' and serves as a sister series to The Occult Tesla. Click here for part 1, here for part 2 and here for part 3.

Culture Wars: Mazzini's Minions Enter the Stage - Edgar Poe as Cultural Warrior Part 4

It is time to repopulate the Federal Republic:

International Public Notice: Why It Must Be an American Republic

The following is part 4 of a new series 'Edgar Poe as Cultural Warrior' and serves as a sister series to The Occult Tesla. Click here for part 1, here for part 2 and here for part 3.

Culture Wars: Mazzini's Minions Enter the Stage - Edgar Poe as Cultural Warrior Part 4

It is time to repopulate the Federal Republic:

International Public Notice: Why It Must Be an American Republic

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.