Marx lived and died as an elitist of the power structure who used this mind control mechanism to place into its adherent's minds to control them. In this sense, Marx is similar to the French hack writer the Rothschild's hired out to develop the conservative ideology. Those who have been programmed with communism are no longer in control of their own free will. America, Canada, New Zealand and Britain are now the targets of this deadly and very destructive non-organic mind programming. Get ready everyone, because now that communism has been unleashed the nihilists will go after the power elite like maggots on rotting meat.

The "Maggot"

Source: big-lies

PSYCHO-ANALYSIS OF KARL MARX by H G WELLS

From The World of William Clissold (1926)

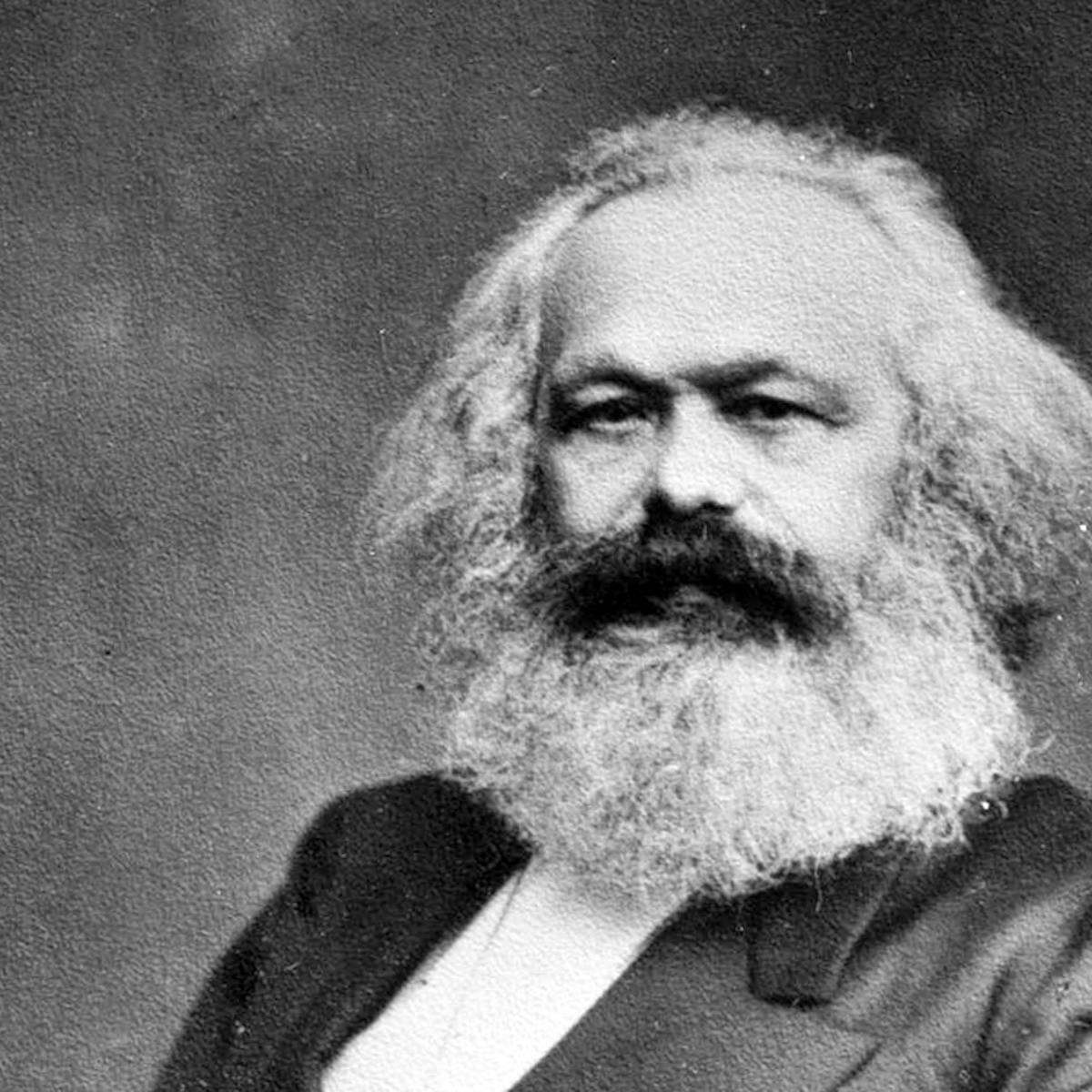

Not psychoanalysis in the Freudian sense—there's nothing here of sex, anal obsessiveness, cannibalism, or whatever else; just snobbishness, peevishness, and a big beard. And intellectually a simplifying insistence on system, envy, and a mightily-muscled mythical proletariat.

Wells was Jew-blind, but had some suspicions of Jews; he considered the entire Jewish 'chosen' tradition had to be removed. The extract here shows quite a powerful mind, completely unaware of the 'Jewish' basis of Marxism. It's a fascinating collection of hints, pieces of evidence, misunderstandings, and partial understanding. It resembles the shape of things before some scientific hypothesis has crystallised.

And see Miles Mathis on Marx (2014) for a more accurate view, showing how successfully Jews hid their agenda.

[Case Against Judaism | Rae West's Home Page]

AND now I can come to the maggot, so to speak, at the core of my decayed Socialism—Karl Marx.

To him we can trace, as much as we can trace it to any single person, this almost universal persuasion, which now Socialist and non-Socialist share, that economically we are living in a definable Capitalist System, which had a specific beginning and may have a definite end, and that the current disorder of human affairs is not a phase but an organised disease that may be exorcised and driven off. Then after a phase of convalescence the millennium. For me he presents the source and beginning of one of the vastest and most dangerous misconceptions, one of the most shallow and disastrous simplifications, that the world has ever suffered from. His teaching was saturated with a peculiarly infectious class animosity. He it was who poisoned and embittered Socialism, so that to-day it is dispersed and lost and must be reassembled and rephrased and reconstructed again slowly and laboriously while the years and the world run by. He it was who was most responsible for the ugly ungraciousness of all current Socialist discussion.

I have always been curious about Marx, the Marx of the prophetic London days, and always a little baffled by the details that have been presented to me. He seems to have led a blameless, irritated, theorising life, very much as Lenin did before he returned to Russia in 1917, remote from mines, factories, railway-yards, and industrialism generally. It was not a very active nor a very laborious life he led; a certain coming and going from organisations and movements abroad in France and Germany must have been its most exciting element. He went to read and work with some regularity in the British Museum Reading-Room, a place that always suggests the interior of a gasometer to me, and he held Sunday gatherings in his Hampstead home and belonged to a club in Soho. He had little earning power, a thing not unusual with economic and financial experts, and he seems to have kept going partly by ill-paid journalism but mainly through the subsidies of his disciple Engels, a Manchester calico merchant. There was a devoted wife and some daughters, but I know very little about them; one married unhappily, a tragedy that might happen to any daughter; of her one hears disproportionately.

PSYCHO-ANALYSIS OF KARL MARX by H G WELLS

From The World of William Clissold (1926)

Not psychoanalysis in the Freudian sense—there's nothing here of sex, anal obsessiveness, cannibalism, or whatever else; just snobbishness, peevishness, and a big beard. And intellectually a simplifying insistence on system, envy, and a mightily-muscled mythical proletariat.

Wells was Jew-blind, but had some suspicions of Jews; he considered the entire Jewish 'chosen' tradition had to be removed. The extract here shows quite a powerful mind, completely unaware of the 'Jewish' basis of Marxism. It's a fascinating collection of hints, pieces of evidence, misunderstandings, and partial understanding. It resembles the shape of things before some scientific hypothesis has crystallised.

And see Miles Mathis on Marx (2014) for a more accurate view, showing how successfully Jews hid their agenda.

[Case Against Judaism | Rae West's Home Page]

AND now I can come to the maggot, so to speak, at the core of my decayed Socialism—Karl Marx.

To him we can trace, as much as we can trace it to any single person, this almost universal persuasion, which now Socialist and non-Socialist share, that economically we are living in a definable Capitalist System, which had a specific beginning and may have a definite end, and that the current disorder of human affairs is not a phase but an organised disease that may be exorcised and driven off. Then after a phase of convalescence the millennium. For me he presents the source and beginning of one of the vastest and most dangerous misconceptions, one of the most shallow and disastrous simplifications, that the world has ever suffered from. His teaching was saturated with a peculiarly infectious class animosity. He it was who poisoned and embittered Socialism, so that to-day it is dispersed and lost and must be reassembled and rephrased and reconstructed again slowly and laboriously while the years and the world run by. He it was who was most responsible for the ugly ungraciousness of all current Socialist discussion.

I have always been curious about Marx, the Marx of the prophetic London days, and always a little baffled by the details that have been presented to me. He seems to have led a blameless, irritated, theorising life, very much as Lenin did before he returned to Russia in 1917, remote from mines, factories, railway-yards, and industrialism generally. It was not a very active nor a very laborious life he led; a certain coming and going from organisations and movements abroad in France and Germany must have been its most exciting element. He went to read and work with some regularity in the British Museum Reading-Room, a place that always suggests the interior of a gasometer to me, and he held Sunday gatherings in his Hampstead home and belonged to a club in Soho. He had little earning power, a thing not unusual with economic and financial experts, and he seems to have kept going partly by ill-paid journalism but mainly through the subsidies of his disciple Engels, a Manchester calico merchant. There was a devoted wife and some daughters, but I know very little about them; one married unhappily, a tragedy that might happen to any daughter; of her one hears disproportionately.

He suffered from his liver, and I suspect him of being generally under-exercised and perhaps rather excessively a smoker. That was the way with many of these heavily bearded Victorians from abroad. He grew an immense rabbinical beard in an age of magnificent beard-growing. It must have precluded exercise as much as a goitre. Over it his eyes look out of his portraits with a sort of uneasy pretension. Under it, I suppose, there appeared the skirts of a frock-coat and trousers and elastic-sided boots. He was touchy, they say, on questions of personal loyalty and priority, often more a symptom of the sedentary life than a defect of character, and the "finished" part of his big work on Capital is overlaboured and rewritten and made difficult by excessive rehandling and sitting over. Examined closely, many of his generalisations are found to be undercut, but these afterthoughts do not extend to Marxism generally.

He tended rather to follow the dialectic of Hegel than to think freely. There had been much mental struggle about Hegelianism in his student days, much emotional correspondence about it, a resistance, and a conversion. He competed with Proudhon in applying the new intellectual tricks to the new ideas of Socialism. He belonged in his schoolboy days to that insubordinate type which prefers revolution to promotion. He was, I believe, sincerely distressed by the injustices of human life, and also he was bitten in his later years by an ambition to parallel the immense effect of Charles Darwin. One or two of his disciples compare him with Darwin; Engels did so at his graveside; the association seems to have been familiar with his coterie before his death. And after three decades of comparative obscurity his name and his leading ideas do seem to have struggled at last—for a time—to an even greater prominence than the work of the modest and patient revolutionary of Down. But though his work professed to be a research, it was much more of an invention. He had not Darwin's gift for contact with reality.

He was already committed to Communism before he began the labours that were to establish it, and from the first questions of policy obscured the flow of his science. What did his work amount to? He imposed this delusion of a System with a beginning, a middle, and an end upon our perplexing economic tumult; he classified society into classes that leave nearly everybody unclassified; he proclaimed his social jehad, the class war, to a small but growing audience, and he passed with dignity into Highgate Cemetery, his death making but a momentary truce in the uncivil disputations of his disciples. His doctrines have been enormously discussed, but, so far as I know, the methods of psycho-analysis have not yet been applied to them. Very interesting results might be obtained if this were properly done.

He detected in the economic affairs of his time a prevalent change of scale in businesses and production which I shall have to discuss later. He extended this change of scale to all economic affairs, an extension which is by no means justifiable. He taught that there was a sort of gravitation of what he called Capital, so that it would concentrate into fewer and fewer hands and that the bulk of humanity would be progressively expropriated. He did not distinguish clearly between concrete possessions in use and money and the claim of the creditor, nor did he allow for the influence of inventions and new methods in straining economic combinations, in altering their range and breaking them up, nor realise the possibility of a limit being set to expropriation by the conditions of efficiency. That a change of scale may have definite limits and that the concentration of ownership may reach a phase of adjustment he never took into consideration. He perceived that big business methods extended very readily to the Press and Parliamentary activities. He simplified the psychology of the immense variety of people, from master-engineers to stock-jobbers and company-promoters whom he lumped together as Capitalists, by supposing it to be purely acquisitive. He made his "Capitalists" all of one sort and his "Workers" all of one sort. Throughout he imposed a bilateral arrangement on a multifarious variety. He simplified the whole spectacle into a process of suction and concentration by the "Capitalist." This process would go on until competition gave place to a "Capitalist-Monopolist" state, with the rest of humanity either the tools, parasites, and infatuated victims of the Capitalists, or else intermittently employed "Workers" in a mood of growing realisation, resentment, and solidarity. He seems to have assumed that the rule of these ever more perilously concentrated Capitalists would necessarily be bad, and that the souls of the Workers would necessarily be chastened and purified by economic depletion. And so onward to the social revolution.

This forced assumption of the necessary wrongness and badness of masters, organisers, and owners, and its concurrent disposition to idealise the workers, was, I am disposed to think, a natural outcome of his limited, too sedentary, bookish life. It was almost as much a consequence of that life as his trouble with his liver. His work is pervaded by the instinctive resentment of the shy type against the large, free, influential individual life. One finds, too, in him that scholar's hate of irreducible complexity to which I have already called attention. In addition there was a driving impatience to conceive of the whole as a process leading to a crisis, to a dénouement satisfying to the half-conscious and subconscious cravings of the thinker. It was under the pressure of these resentments and impatiences—and with the assistance of the Hegelian doctrine which tells us that the Thing-that-is is always shattered at last to make way for a higher synthesis by the Thing-that-it-isn't—that Marxism evolved its prophecy of the ultimate and not very remote victory of the idealised worker. The Proletarian would solidaritate (my word), and arrive en masse, he would crystallise out as Master, and all things would be changed at his coming. He would put down the mighty from their seats and exalt the humble and meek. He would fill the hungry with good things and the rich he would send empty away. The petty bourgeoisie he would smack hard and good. And everyone who mattered to the resentful gentleman who was making the story would be happy for ever afterwards.

It was a wish solidifying into a conviction that gave the world this wonderful and dramatic forecast of the dispossessed Proletarian becoming class-conscious, merging the residue of his dwarfed and starved individuality in solidarity with his kind, seizing arms, revolting massively, setting up that mystery, the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, "taking over" the "Capitalist-Monopolist state" and, after a phase of accommodation, dissolving it away into a confused democratic Communism, the Millennium. It is a dream story of things that are not happening and that are not likely to happen, but it is a very satisfying story for the soul of an intelligent and sensitive man indignant at the distresses of life and living unappreciated in a byway.

Worker It is for the psycho-analyst to lay bare the subtler processes in the evolution of this dream of a Proletarian saviour. Everybody nowadays knows that giant, in May-day cartoons and Communist pamphlets and wherever romantic Communism expresses itself by pictures, presenting indeed no known sort of worker, but betraying very clearly in its vast biceps, its colossal proportions, its small head and the hammer of Thor in its mighty grip, the suppressed cravings of the restricted Intellectual for an immense virility. This Proletarian is to arise and his enemies—and particularly an educated world very negligent of its prophet—are to be scattered. There will then be a rough unpleasant time for the petty bourgeoisie. Things of the severest sort will happen to them. After the upper, they will get the nether millstone grinding into them. ...

The respectable leaders of British Victorian Trade Unionism upon whom Marx sought to foist this monster as their very spit and likeness, seem to have been considerably dismayed by it. They felt so much more like the petty bourgeoisie.

Please go to big-lies to read more.

He tended rather to follow the dialectic of Hegel than to think freely. There had been much mental struggle about Hegelianism in his student days, much emotional correspondence about it, a resistance, and a conversion. He competed with Proudhon in applying the new intellectual tricks to the new ideas of Socialism. He belonged in his schoolboy days to that insubordinate type which prefers revolution to promotion. He was, I believe, sincerely distressed by the injustices of human life, and also he was bitten in his later years by an ambition to parallel the immense effect of Charles Darwin. One or two of his disciples compare him with Darwin; Engels did so at his graveside; the association seems to have been familiar with his coterie before his death. And after three decades of comparative obscurity his name and his leading ideas do seem to have struggled at last—for a time—to an even greater prominence than the work of the modest and patient revolutionary of Down. But though his work professed to be a research, it was much more of an invention. He had not Darwin's gift for contact with reality.

He was already committed to Communism before he began the labours that were to establish it, and from the first questions of policy obscured the flow of his science. What did his work amount to? He imposed this delusion of a System with a beginning, a middle, and an end upon our perplexing economic tumult; he classified society into classes that leave nearly everybody unclassified; he proclaimed his social jehad, the class war, to a small but growing audience, and he passed with dignity into Highgate Cemetery, his death making but a momentary truce in the uncivil disputations of his disciples. His doctrines have been enormously discussed, but, so far as I know, the methods of psycho-analysis have not yet been applied to them. Very interesting results might be obtained if this were properly done.

He detected in the economic affairs of his time a prevalent change of scale in businesses and production which I shall have to discuss later. He extended this change of scale to all economic affairs, an extension which is by no means justifiable. He taught that there was a sort of gravitation of what he called Capital, so that it would concentrate into fewer and fewer hands and that the bulk of humanity would be progressively expropriated. He did not distinguish clearly between concrete possessions in use and money and the claim of the creditor, nor did he allow for the influence of inventions and new methods in straining economic combinations, in altering their range and breaking them up, nor realise the possibility of a limit being set to expropriation by the conditions of efficiency. That a change of scale may have definite limits and that the concentration of ownership may reach a phase of adjustment he never took into consideration. He perceived that big business methods extended very readily to the Press and Parliamentary activities. He simplified the psychology of the immense variety of people, from master-engineers to stock-jobbers and company-promoters whom he lumped together as Capitalists, by supposing it to be purely acquisitive. He made his "Capitalists" all of one sort and his "Workers" all of one sort. Throughout he imposed a bilateral arrangement on a multifarious variety. He simplified the whole spectacle into a process of suction and concentration by the "Capitalist." This process would go on until competition gave place to a "Capitalist-Monopolist" state, with the rest of humanity either the tools, parasites, and infatuated victims of the Capitalists, or else intermittently employed "Workers" in a mood of growing realisation, resentment, and solidarity. He seems to have assumed that the rule of these ever more perilously concentrated Capitalists would necessarily be bad, and that the souls of the Workers would necessarily be chastened and purified by economic depletion. And so onward to the social revolution.

This forced assumption of the necessary wrongness and badness of masters, organisers, and owners, and its concurrent disposition to idealise the workers, was, I am disposed to think, a natural outcome of his limited, too sedentary, bookish life. It was almost as much a consequence of that life as his trouble with his liver. His work is pervaded by the instinctive resentment of the shy type against the large, free, influential individual life. One finds, too, in him that scholar's hate of irreducible complexity to which I have already called attention. In addition there was a driving impatience to conceive of the whole as a process leading to a crisis, to a dénouement satisfying to the half-conscious and subconscious cravings of the thinker. It was under the pressure of these resentments and impatiences—and with the assistance of the Hegelian doctrine which tells us that the Thing-that-is is always shattered at last to make way for a higher synthesis by the Thing-that-it-isn't—that Marxism evolved its prophecy of the ultimate and not very remote victory of the idealised worker. The Proletarian would solidaritate (my word), and arrive en masse, he would crystallise out as Master, and all things would be changed at his coming. He would put down the mighty from their seats and exalt the humble and meek. He would fill the hungry with good things and the rich he would send empty away. The petty bourgeoisie he would smack hard and good. And everyone who mattered to the resentful gentleman who was making the story would be happy for ever afterwards.

It was a wish solidifying into a conviction that gave the world this wonderful and dramatic forecast of the dispossessed Proletarian becoming class-conscious, merging the residue of his dwarfed and starved individuality in solidarity with his kind, seizing arms, revolting massively, setting up that mystery, the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, "taking over" the "Capitalist-Monopolist state" and, after a phase of accommodation, dissolving it away into a confused democratic Communism, the Millennium. It is a dream story of things that are not happening and that are not likely to happen, but it is a very satisfying story for the soul of an intelligent and sensitive man indignant at the distresses of life and living unappreciated in a byway.

Worker It is for the psycho-analyst to lay bare the subtler processes in the evolution of this dream of a Proletarian saviour. Everybody nowadays knows that giant, in May-day cartoons and Communist pamphlets and wherever romantic Communism expresses itself by pictures, presenting indeed no known sort of worker, but betraying very clearly in its vast biceps, its colossal proportions, its small head and the hammer of Thor in its mighty grip, the suppressed cravings of the restricted Intellectual for an immense virility. This Proletarian is to arise and his enemies—and particularly an educated world very negligent of its prophet—are to be scattered. There will then be a rough unpleasant time for the petty bourgeoisie. Things of the severest sort will happen to them. After the upper, they will get the nether millstone grinding into them. ...

The respectable leaders of British Victorian Trade Unionism upon whom Marx sought to foist this monster as their very spit and likeness, seem to have been considerably dismayed by it. They felt so much more like the petty bourgeoisie.

Please go to big-lies to read more.

________

The elite who run this global commercial death cult unleashed Communism on us in the form of Covid. Why, the general asks? Because the communist mind programming the maggot constructed is superior to military psychological warfare. And now that communism has been unleashed look out. It is not going to be able to be controlled.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.