A Request by United States Marine Field McConnell

for

Images Leading To A Proof by Contradiction Of Assertions Below

Plum City Online - (AbelDanger.net)

October 16, 2015

1. AD ASSERTS THAT THE 'LIBRANO' CRIME FAMILY – FOUNDED BY THE LATE PIERRE TRUDEAU IN 1949 – USED PEDOPHILE BLACKMAILERS TO EXTORT PRIVY COUNCIL (PC) AUTHORITY for the ultra vires attack on the United States on 9/11.

2. AD ASSERTS THAT PRIVY COUNCILLORS USED A SERCO 8(A) RED TEAM OUT OF GOOSE BAY to trick US counterparts with a 30 hour ‘blue air’ period and anti-hijacking and 4-minute warning devices in the bait-and-switch war game of 9/11.

3. AD ASSERTS THAT SERCO SET A 9/11 STAND-DOWN TRAP FOR NORMAN MINETA BY FLYING RED TEAM HIJACKERS WITH TIMING, POSITIONING AND NAVIGATION SIGNALS DERIVED FROM THE NAVY MASTER CLOCK.

United States Marine Field McConnell (http://www.abeldanger.net/2010/01/field-mcconnell-bio.html) is writing an e-book "Shaking Hands With the Devil's Clocks" and invites readers to e-mail him images (examples below) for a proof by contradiction of the three assertions above.

The first meeting of the Privy Council before the reigning sovereign; in the State Dining Room of Rideau Hall, Queen Elizabeth II is seated at centre.

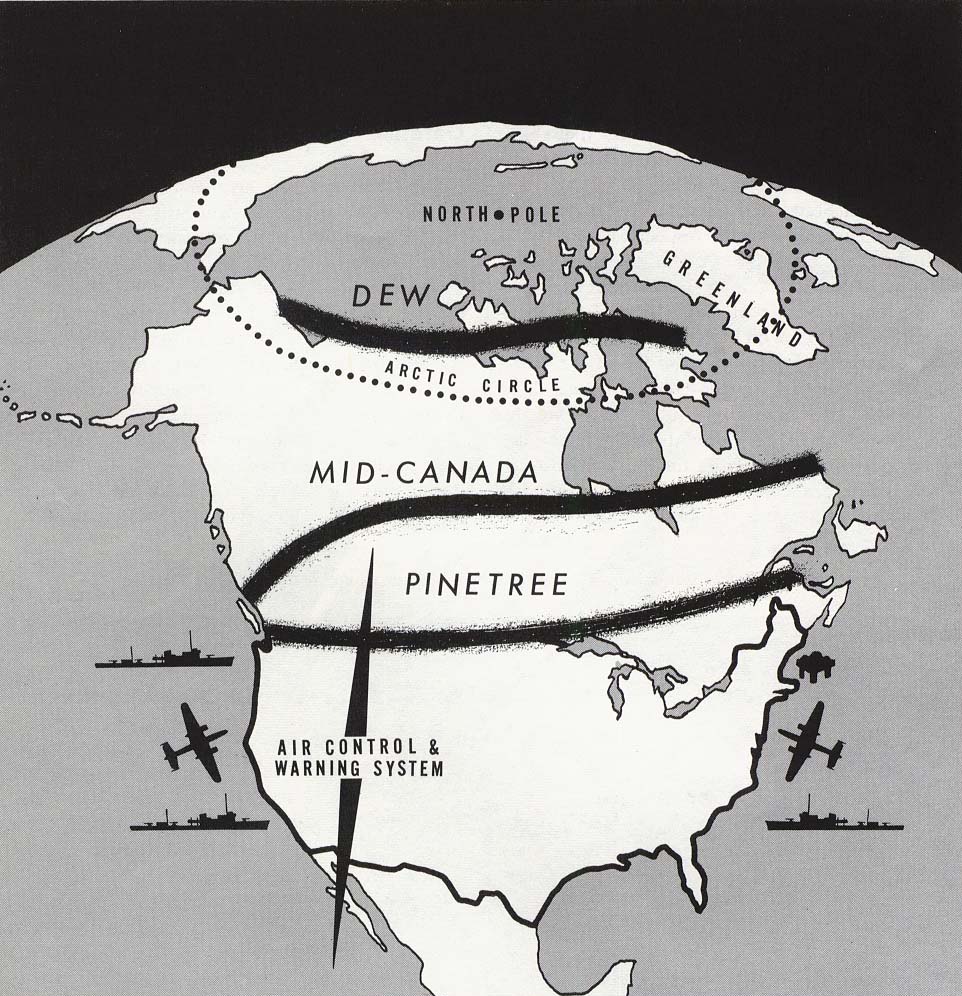

Goose Bay in the middle position for 9/11 attack since WWII!

9/11 Norman Mineta Testifies Dick Cheney ordered a stand down for Flight 77

Privy councillors Collenette and Chretien with Clinton after Mineta stand down.

Run by Serco since 1988 after a name change from RCA GB 1929.

Run by Serco since 1953

USPTO run by Serco since 1994

White's Club Lewes Bombs WWII

Randolph Churchill - White's Club assassin and former member of the SAS/Long Range Desert Group who advised Prince Philip on the role of Goose Bay in mutually assured destruction strategies during Cold War.

The Mayfair Set episode 1- Who Pays Wins

"Institutionalizing Imagination: The Case of Aircraft as Weapons …..The CTC did not analyze how an aircraft, hijacked or explosives laden, might be used as a weapon. It did not perform this kind of analysis from the enemy's perspective ("red team" analysis), even though suicide terrorism had become a principal tactic of Middle Eastern terrorists. If it had done so, we believe such an analysis would soon have spotlighted a critical constraint for the terrorists -- finding a suicide operative able to fly large jet aircraft.They had never done so before 9/11.

The CTC did not develop a set of telltale indicators for this method of attack. For example, one such indicator might be the discovery of possible terrorists pursuing flight training to fly large jet aircraft, or seeking to buy advanced flight simulators.

The CTC did not propose, and the intelligence community collection management process did not set, requirements to monitor such telltale indicators.Therefore the warning system was not looking for information such as the July 2001 FBI report of potential terrorist interest in various kinds of aircraft training in Arizona, or the August 2001 arrest of Zacarias Moussaoui because of his suspicious behavior in a Minnesota flight school. In late August, the Moussaoui arrest was briefed to the DCI and other top CIA officials under the heading "Islamic Extremist Learns to Fly."24 Because the system was not tuned to comprehend the potential significance of this information, the news had no effect on warning.

Neither the intelligence community nor aviation security experts analyzed systemic defenses within an aircraft or against terrorist controlled aircraft, suicidal or otherwise. The many threat reports mentioning aircraft were passed to the FAA.While that agency continued to react to specific, credible threats, it did not try to perform the broader warning functions we describe here. No one in the government was taking on that role for domestic vulnerabilities.

Richard Clarke told us that he was concerned about the danger posed by aircraft in the context of protecting the Atlanta Olympics of 1996,the White House complex,and the 2001 G-8 summit in Genoa. But he attributed his awareness more to Tom Clancy novels than to warnings from the intelligence community. He did not, or could not, press the government to work on the systemic issues of how to strengthen the layered security defenses to protect aircraft against hijackings or put the adequacy of air defenses against suicide hijackers on the national policy agenda.

The methods for detecting and then warning of surprise attack that the U.S. government had so painstakingly developed in the decades after Pearl Harbor did not fail; instead, they were not really tried.They were not employed to analyze the enemy that, as the twentieth century closed,was most likely to launch a surprise attack directly against the United States.

9/11 Commission Report"

Education and the Second World War[edit]

Trudeau earned his law

degree at the Université de Montréal in 1943. During

his studies he was conscripted into the Canadian

Army as part of the National Resources Mobilization Act.

When conscripted, he decided to join the Canadian Officers' Training Corps, and

he then served with the other conscripts in Canada, since they were not

assigned to overseas military service until after the Conscription Crisis of 1944 after

the Invasion of Normandy that June. Before

this, all Canadians serving overseas were volunteers, and not conscripts.

Trudeau said he was

willing to fight during World

War II, but he believed that to do so would be to turn his back on the

population of Quebec that he believed had been betrayed by the government

of William Lyon Mackenzie King. Trudeau

reflected on his opposition to conscription and

his doubts about the war in his Memoirs (1993): "So there was a

war? Tough ... if you were a French Canadian in Montreal in the early

1940s, you did not automatically believe that this was a just war ...

we tended to think of this war as a settling of scores among the

superpowers."[10]

In an Outremont by-election in 1942

he campaigned for the anticonscription candidate Jean

Drapeau (later the Mayor

of Montreal), and he was thenceforth expelled from the Officers' Training

Corps for lack of discipline. After the war Trudeau continued his studies,

first taking a master's degree in political

economy at Harvard University's Graduate School of Public Administration. He

then studied in Paris, France in 1947 at the Institut d'Études Politiques de

Paris. Finally, he enrolled for a doctorate at the London School of Economics, but did not

finish his dissertation.[12]

Trudeau was interested

in Marxist ideas

in the 1940s and his Harvard dissertation was on the topic of Communism and

Christianity.[13] Thanks

to the great intellectual migration away from Europe's fascism, Harvard had

become a major intellectual centre in which he profoundly changed.[14] Despite

this, Trudeau found himself an outsider – a French Catholic living for the

first time outside of Quebec in the predominantly Protestant American Harvard

University.[15] This

isolation deepened finally into despair,[16] and

led to Trudeau's decision to continue his Harvard studies abroad.[17]

In 1947 Trudeau

travelled to Paris to continue his dissertation work. Over a five-week period

he attended many lectures and became a follower of personalismafter

being influenced most notably by Emmanuel

Mounier.[18] He

also was influenced by Nicolas Berdyaev, particularly his book Slavery and

Freedom.[19]Max and Monique

Nemni argue that Berdyaev's book influenced Trudeau's rejection of

nationalism and separatism.[19] The

Harvard dissertation remained unfinished when Trudeau entered a doctoral

program to study under the renowned socialist economist Harold

Laski in the London School of Economics.[20] This

cemented Trudeau's belief that Keynesian economics and social science

were essential to the creation of the "good life" in democratic

society.[21]

Early career[edit]

From the late 1940s

through the mid-1960s, Trudeau was primarily based in Montreal and was seen by

many as an intellectual. In 1949 he was an active supporter of workers in

the Asbestos Strike. In 1956 he edited an important

book on the subject, La grève de l'amiante, which argued that the strike

was a seminal event in Quebec's history, marking the beginning of resistance to

the conservative, Francophone

From 1949 to 1951

Trudeau worked briefly in Ottawa, in the Privy Council Office of the Liberal

Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent as an economic policy

advisor. He wrote in his memoirs that he found this period very useful later

on, when he entered politics, and that senior civil servant Norman

Robertson tried unsuccessfully to persuade him to stay on."

"Jimmy Savile and Prince Charles – The Pedophile Connection

Surprise, surprise –

Prince Charles is potentially linked to the pedophile scandals terrorizing

Europe… I think it is wonderful these scumbags are finally being exposed for

who they really, truly are.

I came across an

article today from 2012, years before the UK Pedophile Scandal really slammed

the papers, and I thought it’s information is worth sharing. It is by

writer Mort Amsel and is titled “Prince Charles Connection To UK Pedophile

Networks" [1].

The article states

(REMEMBER IT IS FROM 2012!):

Fresh on the heels of

the fallout from revelations regarding former BBC entertainer Jimmy Savile and

his unbelievably sickening and innumerable instances of child molestation as

well as the “look the other way” approach taken by the BBC, more and more questions

are now emerging in regards to the connection between Savile and British

Royalty, most notably Prince Charles.

At least, more

questions should be emerging.

Unfortunately,

however, the British mainstream media is deeming Prince Charles and the

rest of his ilk in positions of power and perceived genetic royalty as if they

are beyond reproach. This approach is typical and to be expected, yet it is

also highly ironic considering the fact that such is the same position the mainstream media took with the allegations against

Jimmy Savile for so many years.

As a result of the

Savile affair, mainstream outlets, particularly the BBC, now have a lot of egg

on their faces in the areas of credibility and respect.In short, any

connections placing Prince Charles in an uncompromising position regarding his

connections with Savile or his potential for sharing a penchant for unnatural

relationships with children is being completely ignored if not officially

covered up.

Although Prince

Charles' friendship with Jimmy Savile, allegedly begun when the two met in the 1970s during the

course of working with children’s wheelchair sports charities, is now

well-known, the extent to which the Prince and the Pedophile were connected

appears to go much deeper than the mainstream media reports let on.

Of course, the two having come in contact at a "charity" event for the disabled is not too far-fetched, even if it is being reported by corporate outlets. After all, using children’s “charities” as a hunting ground and a cover for his true motives was a notorious method used by Savile who actually lived in children’s homes and hospitals so as to be closer to his victims. This method is by no means specific to Savile, however, as many other sexual predators and pedophiles know exactly what areas of society to be involved in and what careers to pursue in order to gain access to their victims. Jerry Sandusky stands as a perfect example.

Clarence House, Prince

Charles' spokesman, declined comment on much of the relationship between Savile

and Charles, only claiming that the relationship was mostly a result of their

“shared interest in supporting disability charities."

Supporting charities,

indeed."

"Members of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada use

the title The Honourable if they are ordinary members.

Prime Ministers, Governors General and Chief Justices automatically are given

the title The Right Honourable. While Governors

General have the right to the title Right Honourable upon being sworn into

office they are not inducted into the Privy Council until the end of their term

unless they were previously members of the council by virtue of another office.

Other eminent individuals such as prominent former Cabinet ministers are

sometimes also given the title Right Honourable. Leaders of opposition parties and provincial premier

"Four Days in September

The Environment Canada

forecast for September 11 called for sunny skies and seasonably mild

temperatures.

A labour dispute

between the Government of Canada and the Public Service Alliance of

Canada (PSAC) had been simmering since July. PSAC called a

one-day national strike for the 11th. In downtown Ottawa, Transport Canada

was an obvious location for strike action. Tower C of Place de Ville is

the head office for Transport Canada and home to thousands of employees.

It also happens to be the tallest building in Ottawa. Union members encircled

Tower C with a picket line.

The

planned PSAC strike action brought François Marion and his team of

staff relations and other human resources managers to Tower C early that

morning, around 5:30 a.m. They met to finalize plans for the day ahead.

There were ongoing discussions with the union about issues that had arisen,

including the entry of employees into the building. "Everything was going

well until about 7:30 or 8 o'clock," Marion says. "Then the

picket line hardened and people started having trouble entering the

building."

Place de Ville,

Tower C

|

Anticipating the strike, some Transport Canada staff made a point of getting to work early. People like Jean LeCours, Director of Preventive Security, and Jean Barrette, Director of Security Operations, who was busy poring over a report of a bomb threat at an airport the night before.

Merrill Smith was

beginning his second day of on-the-job training in the Communications Group. A

veteran of more than 20 years at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Smith

had been told that he would find Transport Canada a relatively quiet place

where things ran pretty smoothly and he shouldn't expect any overtime. The

irony of that advice would soon become dramatically clear in the long days and

weeks ahead.

Diana MacTier, a

regional Employee Assistance Program counsellor with Transport Canada, was

busy getting ready to hold an information session to promote a six-week

employee course entitled "Preventing Burnout."

The strike disrupted

operations at Transport Canada but it did not completely bring them to a

standstill.

Transport Minister David Collenette was in

Montreal, delivering a speech to a conference of airport executives from around

the world. Then Deputy

Minister, Margaret Bloodworth, was one block away from Tower C, at

meetings at Industry Canada. Then Associate Deputy Minister, Louis Ranger,

was in Montreal with the Minister. The Assistant Deputy

Minister for Safety and Security, Bill Elliott, was at a conference in

Beijing. A group of Civil Aviation managers was at meetings in Edmonton.

And Julie Mah, then Manager, Policy & Consultation, Explosives

Detection Systems (EDS) Project, was beginning her day just over an hour's

drive east of Ottawa, in Rigaud, Quebec, where she was participating in a

management course.

This air of relative

normalcy was punctured at 8:45 a.m., when American Airlines Flight 11

slammed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center in

New York. Eighteen minutes later, a second passenger plane, United

Airlines Flight 175, struck the South Tower of the World Trade Center. Two

staff relations advisors, Pat McCauley and Eric Daoust, were

monitoring the strike from the Situation Centre on the 14th floor. They stared in stunned disbelief at the

live pictures being flashed across two giant television screens of the second

plane knifing through the South Tower. "You knew that the second

plane was not a replay and it wasn't a movie, although

it could have been," Lyne Landriault, Chief, Staff Relations,

recalled later. "We realized then that what had been the obsession of

our work lives for quite some time [the labour dispute] suddenly… seemed

inconsequential."

The horrible news

spread with lightning speed through Tower C down to the concourse below

and the picketers. Once union leaders and members understood the magnitude of

the events, they were also obviously shaken. Without hesitation, they

immediately stopped the picket lines and went back to work to offer whatever

assistance was necessary.

Jean Barrette was

still reading a bomb threat report when he glanced up at the pictures on the

giant TV screens in the Civil Aviation Contingency Operations centre.

Although the second

plane had not struck yet, he knew that this was no accident. Barrette had been

in the aviation business for 28 years and his gut told him that in broad

daylight and with today's anti-collision equipment, he doubted very much that

this was an accident. "My hunch was that it was a terrorist act."

Some of

Transport Canada's staff members design disaster scenarios. Prior to

September 11, if one of the team had prepared a scenario where suicidal

hijackers would crash their planes into tall buildings, it would have seemed

inconceivable.

At the training centre

in Rigaud, Julie Mah could not believe that a plane had actually flown

into the World Trade Center. It was only after turning on CNN in her

room during the break that she realized it was all too tragically real.

Janet Luloff,

Manager of Security Planning and Legislation, says she will always remember

watching the attack on the second World Trade Center tower, live, in

her Director General's office. Thinking back over the years as part of the

security team, she instinctively knew that the implications were huge and that

if she had time, she would call home and tell her family not to expect to see

her for a while.

Valerie Dufour,

Director General of Air Policy, heard the bulletin on her car radio as she was

driving to work. Her background is not in emergency response; she is a policy

person. But Dufour wanted to help out in any way she could and she just had to

get to the Situation Centre. She would spend 16 to 18 hours a day there

for the next several days.

Louis Ranger will

never forget the two hours he spent in a van with Minister Collenette, as

they rushed from Montreal back to Ottawa. Their driver for the day was Robert

Rivard, a Security Inspector from Transport Canada's Quebec Region.

Marie-Hélène Lévesque, Special Assistant to the Minister, was also with

them.

Ranger remembers:

"Of course we had the radio on, but had not seen the horrible pictures. The

Minister was on the phone with the Deputy Minister and with Sue Ronald,

his Executive Assistant. I was calling all over the place. So was Marie-Hélène.

By the time we had reached Casselman [about 30 minutes east of Ottawa],

most of our cell phone batteries were dead. Maybe that was a good thing. That

gave the Minister time to reflect on the situation. By the time we got to

Ottawa, he knew what he had to do. And so did I."

On September 11

and for the following three weeks, the Situation Centre — or SitCen as it's

known around Tower C — became the nerve centre for everyone involved in

the response to the crisis.

It was the focal point

for all decisions and actions taken by Transport Canada and its many

partners.

The SitCen opened

on the 14th floor of Tower C in the fall of 1994. It's an

ultra-modern facility, equipped with state-of-the-art computer hardware and

custom software, advanced communications, mapping and audio visual equipment,

rows of work stations, and is dominated by two massive projection screens

which, when lowered from the ceiling, take up entire window panels and block

out the daylight.

The SitCen was

designed as a communications centre, capable of coordinating an emergency

response to a huge earthquake on the west coast. The quake, which many experts

believe is inevitable, hasn't happened. However, the SitCen has been

activated many times over the years, including during the ice storm in Ontario

and Quebec and the Swissair disaster near Peggy's Cove.

SitCen employees

answering the phones

|

On September 11, 2001, it was activated again, only this time in response to a scenario that no one had previously imagined possible.

The SitCen was

buzzing with people in no time. People from security, from air policy, and from

communications. Several critical departments and agencies quickly had staff in

the SitCen to lend support to their Transport Canada colleagues.

These included NAV CANADA, National Defence,

the RCMPand CSIS. In addition, telephone links were established with

key staff in other departments including Citizenship and Immigration Canada,

the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency and the Federal Aviation Administration

in the United States. A representative from the United States embassy

was also on hand to help the two countries coordinate their activities. Even

people whose job did not require them to be there insisted on pitching in —

people like Tania Lambert and Anouk Landry, two program officers in

the Security Awareness Division.

Coordinating the

crisis response for Transport Canada was Dr. John Read, who was

filling in as the Acting Assistant Deputy Minister for Safety and Security

while Bill Elliott was in Beijing, China where he was attending a maritime

safety forum. Read was a logical choice, a cool and decisive public service

manager with considerable experience handling emergencies involving dangerous

goods.

The early moments

after the SitCen was activated were somewhat chaotic. And with good

reason. Rumours of further terrorist attacks began proliferating. One had a

bomb going off at the Washington Mall; another reported that the State

Department had been bombed.

These rumours, along

with the constant televised replays of the attacks, helped to feed the

atmosphere of growing fear and uncertainty.

With the attack on the

Pentagon confirmed and the report of a fourth hijacked plane in the skies over

Pennsylvania, the U.S. announced it was sealing off its airspace to all

incoming international flights.

A short time later,

Minister Collenette ordered all civil aviation traffic in Canada grounded.

For John Read and

his response team in the SitCen, this would present just the first of many

colossal challenges.

"We had roughly

500 trans-Atlantic flights and 90 trans-Pacific flights heading our

way," Read recalls. "One to two planes entering Canadian airspace

every minute. With U.S. airspace shut down, we had to decide what to do with

those planes. We had NAV CANADA contact all flights and instruct those

with enough fuel to turn back. The rest would continue flying to

North America and would be diverted to airports primarily on Canada's east

coast, starting with Goose Bay. This process took five minutes to

complete."

The impact of these

critical decisions was felt across government. In practical terms, these actions

instantly generated a new, heavier workload for several departments and

agencies, such as Canada Customs and Revenue Agency,

National Defence, the RCMP and Citizenship and Immigration

Canada.

John Read, for

one, can't say enough about the work ethic and the great contribution of these

organizations. "It was truly instructive to see how the other departments

and agencies very willingly accepted the roles assigned to them without

question, when there was no time to question decisions," Read recalls.

"In my entire career as a public servant, I think this ranks as the finest

example of the government working together as a team, as one seamless unit with

a common sense of purpose."

Of great concern were

the 224 diverted flights fast approaching Canadian airports. The actions

of all those in the SitCen were governed by thoughts such as, 'what

if the terrorist attacks weren't over?' 'Tens of thousands of strangers were

about to land on Canadian soil.' 'Could it be possible that any of those planes

might be hijacked as they neared North America?' 'Could they too be turned

into destructive missiles?' Jean LeCours, one of Read's right-hand aides,

called it a "kind of Armageddon scenario".

They code-named it

Operation Yellow Ribbon. It was the system hastily set up to keep track of the

224 diverted planes and the more than 33,000 displaced passengers on

board.

One by one, the planes

landed in places with names unfamiliar to many of the unexpected guests —

Goose Bay, Gander, and Stephenville, and larger centres such as Moncton,

St. John's, Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Calgary and Vancouver.

The smaller airports had not been built to accommodate such large numbers of

additional aircraft. So the planes were directed away from the terminal

buildings and onto the runways where they were stacked up — almost

sardine-style.

Jim Drummond, a

soft-spoken man who is Chief of Preventive Security Programs, found himself

conscripted into Operation Yellow Ribbon when he walked into the SitCen.

Drummond still remembers his marching orders as if he received them yesterday.

"I was instructed to get in touch with all the airports where these planes

had landed, maintain contact with them and report back to the Deputy Minister

every hour." Drummond says his assignment had its own stresses. "It

was difficult dealing with some of the people at the airports," he says.

"They sounded very harried and were obviously very busy and didn't

appreciate being bothered by us for these status reports."

Vancouver International

Airport handled large amounts of diverted flights and passengers.

|

Although Operation Yellow Ribbon was being coordinated from the Situation Centre on the 14th floor of Tower C in Ottawa, the men and women working in Transport Canada's regions also bore the burden of this massive security effort. Regional Situation Centres across the country went into high gear as employees worked night and day to help manage the situation as it unfolded, and communities opened their arms to passengers as they arrived.

In Vancouver, Brian Bramah, Regional Director of Security and Emergency Preparedness, recalls in particular how everyone worked together, including processing over 8,500 passengers from the 33 diverted flights which came to Vancouver. "I am proud to be part of an organization that worked so well with other government departments and airport operators. Staff all stepped forward to get the job done as the planes came in," he says. Bramah also remembers that the whole community pulled together too. For example, cruise ships in the port of Vancouver became hotels for passengers who couldn't fly out.

Perhaps the largest impact on Transport Canada's regional operations occurred in Atlantic Canada, as airports there accepted more than half of the diverted flights.

Ozzie Auffrey, Regional Director of Security and Emergency Preparedness in the Atlantic Region, puts the magnitude of the job in stark context. "On September 11, a total of 126 unexpected aircrafts suddenly landed in the Atlantic Region, carrying thousands of passengers from all over the world."

Some 44

international flights carrying 8,800 passengers were diverted to Halifax

International Airport.

|

Civil Aviation Inspector Garry Noel, who arrived in the small Newfoundland community of Stephenville the day after the terrorist attacks, stayed to help out until the last diverted plane left five days later. "In normal times, the security staff at the Stephenville Airport screens about 37 passengers per day," says Noel. "When I got there on the 12th, there were more than 1,700 passengers who had landed aboard eight wide-bodied aircraft who had to be screened. That's almost 50 times the usual volume of people passing through the Stephenville Airport."

Tracking where the

flights had landed was only one part of this formidable security operation. All

passengers were to be confined to their aircraft, assessed and searched. That's

tens of thousands of passengers. Every piece of baggage had to be searched and

matched against its owner. It was only once this process was completed that

passengers were free to leave the planes. For many travellers, it meant being

cooped up for 16 hours or more.

Passengers were not

allowed off the planes at Halifax International Airport until the evening of

September 11th. That morning, 40 international flights were diverted

to Halifax carrying about 8,800 passengers. Senior Communications Officer

Paul Doucet says that electronic communications complications with the aircraft

compounded the wait for the stranded travellers. "Before they could

deplane, we needed an accurate head count and so we went from plane to plane to

get the tally directly from the crew," Doucet recalls. "The count was

necessary to ease the customs clearance bottleneck and to enable local

authorities to arrange transportation and accommodation for the

passengers."

September 11th

was a long day for Doucet — as it was for Transport Canada employees

across the country — and there would be little respite in the days to follow.

"I arrived at the airport at about 1:00 p.m. and didn't leave for

home until 3:00 a.m. the next morning. At about 8 a.m., I returned to

the airport and a changed world."

Needless to say, the

totally unfamiliar surroundings and the confusing news reports from the

disaster sites in the U.S. caused some emotional moments. In Gander, Civil

Aviation Inspector Rick McGregor described the scene as tensions were

running high at a meeting to brief crew members on the situation in the U.S.

"At one point, a young aircraft commander stood up and began talking to

the crews, to explain the gravity of the situation. As he was talking, he kept

breaking down in tears. He had lost some friends in the

World Trade Center. At that point, the horrible reality set in,

everyone calmed down and returned their focus to the situation at hand."

Across Atlantic

Canada, those dark days of September 2001 were partly offset by the many

poignant displays of peace and friendship. In the communities that received

diverted flights, there were spontaneous acts of generosity and compassion toward

the thousands of stunned strangers who had suddenly arrived out of the heavens.

The people of Gander

gained an international reputation for gracious hospitality overnight.

Normally, the town has a population of about 10,000. As one local resident

put it, "On September 11th, we had 38 aircraft with a total of

6,656 people drop by for coffee, then stay for three or four days."

Gander Mayor

Claude Elliott says he'll forever be proud of how quickly the people of

Gander mobilized to reach out to the stranded passengers and make them feel at

home. "Even in the beginning… we didn't know who was on those planes and

we tried to discourage people from taking them into their homes, but

Newfoundlanders being Newfoundlanders, a lot of people didn't listen. They just

took them into their homes anyway."

Diverted planes

stacked up at Gander Airport.

|

Civil Aviation Inspector Roger Auffrey spent several days during the crisis lending a hand to the thinly-stretched security team in Gander. Auffrey says the genuine generosity that he saw Atlantic Canadians show perfect strangers has left a rich legacy that will last a long time. "Gander is only one example," he says. "A Web site called www.thankstogander.de

One of the more touching

expressions of gratitude came from the German air carrier, Lufthansa. The

airline renamed one of its planes Gander-Halifax, in recognition of how the two

Canadian cities took care of passengers stranded by the September 11th

terrorist attacks. To help celebrate the event, Lufthansa flew 20 people,

including airport and municipal staff, to Germany.

There is no question

that September 11 placed enormous demands on the people responding to the

crisis. The job of reopening Canadian airspace would be equally, if not more,

overwhelming.

Pressure was building

to get commercial aviation airborne again. But before the planes could take

off, new and enhanced security procedures had to be drafted and put into

effect. That responsibility fell to Hal Whiteman, then Director General of

Security and Emergency Preparedness, who led a team of experts in rewriting the

rulebook for aviation security so that the country's skies would be safe from

potential terrorist threats in the future.

The new rules would

also be totally different from the package of regulations that governed

Canadian airspace before September 11. And they would have to be

compatible with the corresponding new regulations being developed by American

transportation authorities.

Usually, it takes two

years to process one set of new security regulations. The people in

the SitCendidn't have two years. The government wanted air traffic resumed

in a matter of days. The time lines would have to be compressed significantly,

the process would have to become a lot more flexible to get the job done. In

the two weeks following September 11, Transport Canada processed ten

sets of new security regulations at a rate of about six hours per regulation.

There were scores of

new regulations, including new restrictions on certain items that could no

longer be taken on board aircraft.

Jean LeCours

remembers hours of debate about whether to ban all knives, including steak

knives. "We had a discussion about the definition of a steak knife. Then

another discussion about the definition of a plastic steak knife, but not a

plastic butter knife."

Read says flexibility

was key to getting the job done. He says people kept turning up in

the SitCenoffering to help and they were flexible enough to step in and do

a particular job.

"Sometimes, people were mismatched with respect to their

status within the department as to who was in charge." Read's favourite

example was having a junior assistant requesting assistance from a senior

manager from a non-security area of the department who had volunteered to help.

The senior manager completed the task and came back and asked if there was

anything else that needed to be done.

As if the pace inside

the Situation Centre was not frenetic enough, somebody gave out, on national

television, the phone number that was being used to answer questions from air

operators on the raft of new security enhancements.

The number served

several lines and once it was released, it triggered an avalanche of calls. At

its peak, there were an estimated 5,000 calls a day. They were coming in

so fast they almost overwhelmed the staff. Everyone, it seemed, had a phone

glued to each ear.

There were hundreds of

media calls, asking about new security enhancements and plans to reopen

airspace. There were calls from concerned members of the public, wondering

about the location and condition of grounded friends and family members.

Some calls were of the

bizarre breed, like the 20 or so from angry dog owners who were told that

the initial ban on air cargo meant that they would not be permitted to fly

their animals to a dog show in London, Ontario.

Perhaps the most

off-beat call of all was fielded by communications officer Peter Coyles.

He remembers speaking to an elderly woman who suggested that all passengers

show up for their flights naked so they would not be able to conceal weapons.

There was also a very

tender moment when a call came in for Jean LeCours. LeCours had two phones

going at the same time and couldn't take the call. So, Valerie Dufour took

it instead. LeCours' wife was on the other end of the line. September 11

was his wedding anniversary. Dufour slipped the message to her colleague.

"It's your wife. She just wants you to know she loves you."

One of the more

interesting subtexts to the story about the fallout from September 11 was

the emotional and psychological impact the disaster was having on the people

responding to it.

Inside

the SitCen, they were too focused on managing a crisis to indulge their

emotions. So, what happens to those emotions? "They get parked," says

John Read. "Because from the moment we walked in there, we were

busy."

Jean LeCours

likens it to the "fog of war." "I have seen TV coverage of

September 11 subsequently and it's like I'm watching it for the first time

because we were too busy to watch TV."

Valerie Dufour

has a similar take. "We were just dealing with stuff. I think people are

'copers'. I've had my share of crises in life and I know that when you are busy

just trying to cope, you can't be busy indulging your own personal emotions at

the same time."

Then Deputy Minister

Margaret Bloodworth remembers asking someone to turn off the TV during the

first week or two when the shocking images from New York were being played

over and over. "I can't afford to watch this, can't afford to let yourself

be drawn into this huge tragedy. There was too much to do to let it affect you

but you can not escape that forever."

Away from

the SitCen and away from Tower C, some people were able to feel

the emotional aftershocks.

Communications officer

Karyn Curtis felt physically drained when she got home around midnight

after a full day on the 11th in the SitCen. She was out like a

light. She got up at 5:00 a.m., made herself a coffee, turned on CNN and

opened the paper. The paper had a photo of people holding hands,

100 floors up in the Twin Towers, and jumping to their deaths to

avoid being burned to death. That's when the full scale of the terrorist

attacks sunk in for Curtis. "I thought that could have been anyone, it

could have been us and our building, it could have been my brother or somebody

I know. I just lost it, I simply dissolved. I sat on my sofa and cried for

about 20 minutes. Then I went off to work and another day in the SitCen."

The implications of

September 11 came to Jim Drummond in a haunting kind of way as he was

heading home the day after the attacks. The drive takes him by Ottawa

International Airport. On that particular day, Drummond was paying more

attention to the sounds of the airport than he had done before. "I never

really noticed the noise before, but I sure noticed the quiet," he

remembers. "Nothing was flying, everything was shut down. It was truly

eerie."

"Stand down

One common view

amongst many 9/11 researchers is that the hijacked planes should not have been

able to reach their destinations. The air defence system would have stopped

them under normal circumstances, they claim, therefore perhaps those defences

had been ordered to stand down. And they point to the account of Norman

Mineta as possible evidence. Here's David Ray

Griffin in the updated

second edition of The New

Pearl Harbor:

… An interview with The Daily Californian

confirms that Jane Garvey stayed in Mineta's

conference room until after the second impact at the WTC, and included the

detail that "the White House is only 7 minutes away" from Mineta's

office:

DC: What was your day

like on September 11?

NM: That morning, I

was having breakfast with the Deputy Prime minister of Belgium Isabelle Durant.

Mrs. Durant is also the minister of transport for Belgium. So Jane Garvey, the

administrator of the FAA and I were having breakfast with her in my conference

room.

My chief of staff then

came in and said, 'Mr. Secretary, can I see you?' The television was on and

obviously it was the World Trade Center with all this black smoke coming out of

it. So I asked John, 'What the heck is that?.' And he said, 'Well we don't

know. We have heard explosion, we have heard the possibility of an airplane

that went into the building.' And so I said, 'Keep me posted,' and I went back

into my breakfast meeting. I explained to Mrs. Durant what was going on.

Then in about five or

six minutes, the chief of staff came back in and said, 'Mr. Secretary, may I

see you again?' He said at that point that it has been confirmed it was a

commercial airliner that went into the World Trade Center. And as I was

standing there watching the television set, all of a sudden from the right side

of the screen came a gray object and then it sort of disappeared and the next

thing, from the left of the screen was this white yellow orangey billow of

cloud coming out of the left side of the screen, so I ran into the conference room

and told Mrs. Durant I was going to have to leave and take care of whatever

this was about.

I told Jane to come

back in with me, and soon after that, I got a call from the White House saying

for me to get over there right away. So I grabbed some papers, grabbed some

stuff and went to the garage. I got in my car and went over to the White House.

Its only seven minutes away. I drove into the White House grounds, and everyone

was running out of the White House, running out of the Executive Office Building.

And I said to the

people with me, 'Is there something wrong with this picture? We are driving

into the White House and everyone else is running out of it. So I went into the

White House and was briefed by Dick Clark of the National Security Council and

he said, 'You have to get over to the Presidential Emergency Operation Center

to be with the vice president.' ...

We started to monitor

what was going on. We knew that there were now two airplanes that had gone into

World Trade Center 1 and World Trade Center 2, and I had a direct line set up

with the FAA.

Someone came in and

said, 'Mr. Vice President, there is a plane 50 miles out.' I asked our FAA

people, 'Can you see an aircraft coming in 50 miles out?' and they said, 'Yeah,

we're tracking it, but the transponder is off, so we don't know what the

identification of that airplane is.' Pretty soon the same person came in and

informed the vice president, sitting right across from me at the conference

table, that the airplane is 30 miles out. I asked the FAA about it and they

said, 'Yeah, we know where the plane is, but we don't know who it is.'

Then they came in and

said it was 10 miles out. Soon after that, I was talking to the deputy director

of the FAA, and he told me they had lost the target off the screen. Soon after

that, then, the vice president was informed that there was an explosion at the

Pentagon. So I was trying to relate with the air traffic controllers where that

plane went to see whether it was close to the Pentagon. The radar is very

difficult to pinpoint it to a ground location.

But while I was

talking to the FAA, someone broke into the conversation and said, 'Mr.

Secretary, we have just had confirmation from the Arlington County Police

Department that they saw a commercial airliner-an American airline-go into the

Pentagon.

Well, its like

anything else, if you see one of something occur you consider that an accident.

But when you see two of the same thing occur then you know that there is a

pattern or a trend. In this instant we had three of the same thing occur, and

that is a program or a plan. So I then informed the FAA to bring all the

airplanes down.

I said, 'Any airplanes

coming into the Eastern seaboard, turn them around and get them out of the

Eastern seaboard heading west. Any planes heading west, have them go on to

their destination if they are close by. But in any event bring all the

airplanes down."

At that point we had

something like 4,836 airplanes in the air and with the skill of the air traffic

controllers and the professionalism of the flight deck crew, the pilots and

co-pilots and the professionalism of the flight cabin crews, they were able to

bring those 4,836 airplanes down in about two hours time, safely and without

incident.

Later on that morning,

I talked to the Minister of Transport in Canada, David Collenette, and said, 'I

have over 200 airplanes coming in from overseas points, and I need you take in

these airplanes.' And they did. They took in over 200 airplanes that day. Their

population went up by over 19,000 people and they very graciously and

generously accommodated those airplanes and passengers. A lot of people were

stuck there until Saturday.

http://web.archive.org/web/

http://web.archive.org/web/

"David Collenette on 9/11

The former transport

minister on deciding who to ground and who could fly on Sept. 11, 2001

David Collenette

September 7, 2011

Wind up your speech.

There has been a tragedy.” This hastily handwritten note, placed on the lectern

as I delivered the keynote address at a conference of international airport

executives, heralded the longest day of my political life. It was Sept. 11,

2001.

I had gotten up at 5

a.m. to take a Transport Canada Citation jet to Montreal, a groggy start to

another long ministerial day. The conference should have been routine. But just

after 9 a.m., the audience became restless. This was not unusual for a

politician giving a speech; still I was puzzled. For the most part, people had

appeared quite interested.

I continued to speak

while reading the note, which instructed me to talk to assistant deputy

minister Louis Ranger and avoid the media. I feared the worst, probably a

serious accident, which Louis did confirm: at 8:45 a.m. a plane had flown into

the World Trade Center in New York. I immediately sensed some type of terrorist

act had occurred, since passenger jets just don’t crash into tall buildings if

they are in trouble. There are all kinds of emergency procedures for pilots:

landing at the nearest airport or ditching in water around Manhattan.

I gave one of the most incoherent media

scrums of my career. I groped for words because I did not have the facts and

could not say what was really going through my mind. I managed to excuse

myself, saying I had to catch a plane to Toronto.

As we made our way to

the van waiting to take us to the airport, we learned from our deputy minister

in Ottawa, Margaret Bloodworth, that a second plane had hit the other tower.

Before too long there would be confirmation of two more crashes, at the

Pentagon and a field in eastern Pennsylvania. Departmental contacts in

Washington said all airports may be closed. We knew this was a crisis and

agreed to head back to Ottawa, about a two-hour drive.

Within a matter of

minutes we heard again from the deputy: my U.S. counterpart, Norman Mineta, had

grounded all flights. Those in U.S. airspace were required to land at the

nearest airport, and any planes attempting to fly across the border would be

forced to land, or possibly shot down by the U.S. Air Force. Within minutes an

aerial wall had been erected around the United States of America, and Canada

found itself on the front line.

This was

unprecedented, and I had a sinking feeling. Should we follow the American lead?

What should we do about the flights in international air space that were now

approaching Canada? It was a logistical nightmare: Mineta’s order was issued at

9.45 Eastern Daylight Time—"rush hour" over the Atlantic. More than 500 planes

with an estimated 75,000 people on board were en route to North America.

The U.S. decision was

made, naturally, with great haste, and was apparently oblivious to a key fact.

The International Civil Aviation Organization allocated jurisdiction over the

western portion of the North Atlantic to NavCanada, our air traffic control

organization, and over the eastern section to the U.K. The United States

actually has no jurisdiction over the area most transatlantic flights traverse;

it only controls the 12 nautical miles directly off its coast.

Nevertheless, there

was no time to ponder the finer points of aviation jurisdiction: every 90

seconds an aircraft was entering Canadian airspace seeking clearance to land.

Under the Aeronautics Act the transport minister is the only person with the

statutory authority to issue emergency orders, but I was in a van barrelling

along Highway 417 toward Ottawa, alone except for Louis and my assistant,

Marie-Helen Levesque. There was fear in their eyes, and I knew then I had to

set the tone and provide leadership. I was a political veteran with a lot of

cabinet experience and at that point had been minister of transport for four

years, yet nothing had prepared me for the ordeal we now faced.

We could only

communicate with Ottawa via the three mobile phones we had between us (the

BlackBerry was still a future technology), which meant that Margaret and others

at headquarters were forced to come up with options, explain the ramifications

to me, then get my decision, all within minutes. Under the authority of the

Aeronautics Act we agreed that I would order a number of measures. All flights

that had yet to take off were grounded, but unlike the U.S., we granted

permission for all flights already in the air to proceed to their final

destination. This provided minimum disruption to passengers.

But what about flights

over the Atlantic, most originally destined for the United States and now

approaching Canadian airspace? We instructed NavCanada, in conjunction with the

British Civil Aviation Authority, to ascertain the geographical position of

each plane to determine how many could be ordered to return to Europe.

Evaluations were made with astounding speed. In little more than five minutes,

more than 250 planes, most at 40,000 feet, were ordered to make a U-turn

mid-ocean. But this still left another 224 that were past the point of no

return.

The U.S. Federal Aviation

Administration had decided they were too risky to allow into American airspace.

We had no way of knowing who was on the planes, although we had started to

receive intelligence reports of the possibility of terrorists on board some of

them. In addition, as news of the attacks in New York was broadcast, there were

bomb threats at Canadian airports. Were these real, or just coming from those

playing sinister games? We could not assume anything other than the worst.

Accepting these aircraft might put Canadian lives at risk, but the alternative

was unthinkable: planes running out of fuel and crashing. Canada had to accept

them and the risks.

As the van sped along

the highway, we had to decide where these planes would land. In the east,

Montreal and Toronto were the largest airports with the best infrastructure,

but the possibility of more terrorists on board raised the spectre of crashes

into the downtown towers of Canada’s two largest cities. Another concern was

that once planes were given the direction to land at Montreal or Toronto, any

hijackers on board could easily take them off course and approach nearby

American cities such as Boston, Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, Cleveland or

Detroit before fighter jets could intercept the planes.

Our only option was to

land most flights at designated airports in Atlantic Canada, where the security

risk was lower. Throughout the Second World War, the Maritime provinces and

Newfoundland and Labrador, then a British colony, were major staging areas for

troops and supplies going to Britain. There was an abundance of airports with

long runways ideal for receiving a large number of planes.

We also had to deal

with the Pacific. The volume of air traffic at that time of day was not as high

but there were still 90 flights en route to North America and many did not have

the fuel to get back to Asia. There was significant risk to landing planes in

Vancouver, given the population density and the proximity of the airport to the

downtown area. But other West Coast airports had relatively short runways and

minimal infrastructure. Vancouver that day took in 33 planes, the third-largest

number next to Gander and Halifax, which received 38 and 40 respectively.

The decisions I took

that morning were arbitrary and without reference to my colleagues or the prime

minister, an extreme oddity given the normally turgid “machinery of

government.” The context was bizarre, to say the least—thousands of lives were

being turned upside down by the one person with authority to act, who was

communicating these decisions via cellular phone while travelling past the

gentle foothills of the Laurentians! At one point I looked out at the beautiful

countryside and thought, “This is surreal, what is going on here? Who was

behind these attacks, and why?"

When I arrived in

Ottawa, I was briefed by the deputy, who asked me to meet with the crisis team.

At the time, Transport Canada and National Defence were the only two government

ministries with operations centres. In 1994, Transport Canada also opened a

state-of-the-art Situation Centre to provide emergency communications and

coordination of disaster response. It had been deployed after the 1997 Swissair

crash off the coast of Nova Scotia and the ice storm of 1998. Usually "Sit Cen"

had minimal staff, but within the past two hours Margaret had seconded a number

of key officials from the aviation and security branches of Transport Canada.

They were joined by staff from NavCanada, National Defence, the RCMP and the

Canadian Security and Intelligence Service. Telephone links had been set up

with Immigration and Citizenship Canada, the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency,

and the Federal Aviation Authority in Washington. An observer from the U.S.

Embassy was present. The Sit Cen’s mission had quickly been named Operation

Yellow Ribbon.

As I entered the room,

I was amazed at the orderly, efficient buzz of activity, yet there was tension,

too, and strained looks. My message was brief: we were all part of one team

facing an enormous challenge, the government counted on their professionalism,

and they had my full support.

Just before 1 p.m. I

went back to my office. My executive assistant, Sue Ronald, said I should watch

the news. As the first crash appeared on the screen, my chest tightened at the

sight of the impact, followed by the unbelievable belching up of fire and

smoke. Then the second tower was hit, followed by the image of both towers

crumbling in one last gasp to the ground. I looked out the window of my office

toward the Parliament Buildings and the majestic Peace Tower and tears welled

up. I abruptly switched the television off. It would be wrong to be caught up

in the emotion. I needed to make dispassionate, reasoned judgments. There would

be time to grieve later.

We had closed Canadian

airspace to all but emergency and humanitarian flights, but officials in the

Sit Cen were called upon to authorize exceptions. In most cases, such as

enabling medivac flights or those required to transport federal government

personnel to Atlantic communities to assist with the processing of thousands of

stranded passengers, the decisions were straightforward. Others were not. The

head of a Chicago-based company whose responsibilities included supplying grief

counsellors to those affected by aviation tragedies, was grounded in Newfoundland.

Canadian permission for his company plane to fly was granted, but the U.S. was

making no exceptions. Flights crossing into American air space would be shot

down, no questions asked. So we cleared his plane to Sarnia, where he took a

car to Chicago. Later we learned 200 of the company’s staff in its World Trade

Center office had died in the attacks.

A number of requests

ended up on my desk. Some were from those in the business community trying to

work political connections. Others were from colleagues on both sides of the

House of Commons who wanted to get back to Ottawa using chartered aircraft. One

senior Liberal wanted permission for a chartered jet to land at Montreal; it

was carrying the body of a close family member from New York City who had died

unexpectedly in Israel. The Americans refused permission to land at Newark and

my friend wanted to take the casket by car from Montreal to New York. Despite

the family’s anguish, I had to say no.

But I also made some

exceptions. Foreign minister John Manley, who was on an Air Canada flight en

route from Frankfurt to Toronto, would be needed to deal with the wider issues

that were coming into play.

Robert Milton, CEO of

Air Canada, was stranded in London at a critical time, when more than 300 of

the airline’s planes were grounded, many overseas. My instinct was to grant

permission.

At about 1:20 p.m.,

the prime minister called. He was supportive of the difficult decisions we were

making, but did surprise me with his assumption that flights could be running later

in the day. I told him it was going to be no easy task to restart things.

First, we had to examine all of our safety and security measures to determine

if the calamitous events warranted immediate rule changes. Second, we would

have to reopen the skies in concert with the U.S. A number of Canadian aircraft

were locked down at American airports; in addition, some long-haul domestic

flights to Eastern and Western Canada routinely fly over U.S. territory. I am

not sure the PM liked my answer, but said I should do my best to return to

normal schedules.

I asked if he was

going to have a cabinet meeting. He said no. Events were moving too fast and I

had the authority to continue making transportation decisions. Besides, there

were not enough ministers in Ottawa to have a quorum, something he was not too

happy about and something that he would deal with in the future. I told him I

had approved John Manley’s return as well as that of Lawrence MacAulay, the

solicitor general, who was coming back to Ottawa from Nova Scotia on an RCMP

aircraft. Jean Chrétien was always businesslike, so he ended the conversation

quickly, saying I should get back to work.

At about 4 p.m. an

emotional Norman Mineta called. He and his colleagues, including president

George W. Bush, were acting with lightning speed. The stress was easy to detect

in his voice. He thanked me for the efforts of the Canadian government and was

deeply grateful to the thousands of Canadians who had turned their lives inside

out by welcoming so many strangers stuck at our airports. I felt an immense

pride in what Canada was doing to help our American friends.

But the stranded

passengers, many of whom were confined to aircraft for up to 16 hours or more,

created a huge logistical challenge. They could not be allowed off the aircraft

until normal immigration and customs procedures were followed; given the

security concerns, this entailed more stringent screening, including more

extensive interrogation and searches. Large numbers of immigration, customs,

RCMP and security intelligence officers had to be transported to Atlantic

Canada—in most cases via DND and Transport Canada, which had the largest

fleets. The stress placed on communities and on various provincial governments

forced to accept thousands of unexpected visitors was enormous, yet no one

complained or argued about financial compensation. Canadians were pulling

together in a remarkable way.

As the afternoon wore

on I became concerned that there had been no official reaction from the

government. When the prime minister did give a news scrum he expressed sympathy

to our American friends for the horror that had taken place, but the situation

was evolving so quickly that questions became more technical than he was

briefed to answer. Unfortunately, the general nature of his comments drew

unfair criticism from some quarters.

At Transport Canada,

we were being inundated with calls from media outlets. We argued with the

communications people in the Prime Minister’s Office that someone needed to

give a detailed response not only to the media but to families of stranded

travellers. There was considerable push back. By 6 p.m., we had received more

than 225 requests, and we needed to get answers out. Finally, we told them we

were going ahead and sent out a news release in time for evening newscasts and

morning newspapers.

Looking back at the

Canadian response, I continue to be amazed at how the behemoth that is

government acted so nimbly. Experts, notwithstanding their rank, gave orders to

top brass and were obeyed. In a culture that invented the “paper trail,” we

adopted a paperless model. Nothing was written down. All briefings were oral.

We relied on personal relationships to get things done. Everyone shared

knowledge. No one held back. The informal relationships and comradeship

developed and nurtured over the years carried the day.

At the time of the

attacks, Transport Canada had a solid organizational structure, with

well-tested rules and reporting relationships. Yet within minutes we were in

unknown territory, where decisions had to be made quickly. To paraphrase former

U.S. president Harry Truman, the buck on that day did stop with us.

Thank God we got it

right."

"David Michael Collenette, PC (born June 24, 1946) was a Canadian politician from

1974 to 2004, and a member of the Liberal Party of Canada. A graduate from York University's Glendon College in 1969, he subsequently

received his MA from in 2004. He was first elected in

the York East riding of Toronto to the House

of Commons on July 8, 1974,

in the Pierre Trudeau government.

Collenette served as a

Member of the Canadian House of Commons for more than 20 years. He was elected

five times and defeated twice. He served in the Cabinet under three prime

ministers - Pierre Trudeau, John Turner and Jean Chrétien. He held several portfolios:

Minister of

State-Multiculturalism (1983–84);

Minister of National

Defense (1993–96);

Minister of Veterans

Affairs (1993–96);

Minister of Transport

(1997–2003) and

Minister of Crown

Corporations (2002–03).

During the

constitutional debates of the early 1980s, he served as Parliamentary Secretary

to the Government House leader and was assigned by the government to

Westminster to represent Canada's interests."

"Super Serco bulldozes ahead

By DAILY MAIL REPORTER

UPDATED: 23:00 GMT, 1 September 2004

UPDATED: 23:00 GMT, 1 September 2004

SERCO has come a long

way since the 1960s when it ran the 'four-minute warning' system to alert the

nation to a ballistic missile attack.

Today its £10.3bn

order book is bigger than many countries' defence budgets. It is bidding for a

further £8bn worth of contracts and sees £16bn of 'opportunities'.

Profit growth is less

ballistic. The first-half pre-tax surplus rose 4% to £28.1m, net profits just

1% to £18m. Stripping out goodwill, the rise was 17%, with dividends up 12.5%

to 0.81p.

Serco runs the

Docklands Light Railway, five UK prisons, airport radar and forest bulldozers

in Florida.

Chairman Kevin Beeston

said: 'We have virtually no debt and more than 600 contracts.'

The shares, 672p four

years ago, rose 8 1/4p to 207 1/4p, valuing Serco at £880m or nearly 17 times

earnings.

Michael Morris, at

broker Arbuthnot, says they are 'a play on UK government spend' which is rising

fast."

"Defence Serco supports the armed forces of a number of countries around the world, including the United Kingdom, United States and Australia, working across land, sea, air, nuclear and space environments. Our mission is to deliver affordable defence capability and support to the armed forces. We work in partnership with our customers in government and the private sector to address the cost of defence, both financial and social, delivering affordable change and assured operational support services.

In the UK and Europe:

Serco manages the UK Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) as part of a consortium with Lockheed Martin and Jacobs. AWE is one of the most advanced research, design and production facilities in the world, developing the sophisticated materials, quantum physics and computer modelling vital to the safe and effective maintenance of the UK's nuclear deterrent. AWE experts also play a leading role in nuclear non-proliferation and international nuclear security.

We enable the Royal Navy to move in and out of port at HM Naval Bases Faslane, Portsmouth and Devonport for operational deployment and training exercises. Managing a fleet of over 100 vessels, we operate tugs and pilot boats, provide stores, liquid and munitions transportation and provide passenger transfer services to and from ships for officers and crew.

We provide facilities and information systems support to the MoD's Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl), the UK government's leading defence research establishment, including a £400m programme to rationalise the Dstl estate. We also provide facilities management services to the Defence Estates in support of the UK military presence in Gibraltar.

Serco provides extensive engineering and maintenance support to UK military aviation, including to the Fleet Air Arm and Royal Air Force, working on over 16 military aircraft types, in addition to the logistical support services at RAF bases across the country, including Brize Norton, Lyneham and High Wycombe, the Headquarters of Air Command.

Our space and security specialists provide spacecraft operation and in-theatre support to the Skynet 5 secure military satellite communications network; we maintain the UK's anti-ballistic missile warning system at RAF Fylingdales and support the UK Air Surveillance and Control System (ASACS); Serco also supports the intelligence mission of the MoD and US Department of Defence at RAF Menwith Hill.

Serco enables the training of national security personnel through its services at the Defence Academy of the United Kingdom, the MoD's world class institute responsible for educating the military leaders of tomorrow; we train all of the RAF's helicopter pilots at the advanced training facility at RAF Benson; and we manage the Cabinet Office's Emergency Planning College, the government's training centre for crisis management and emergency planning.

In the UK, we also developed an approach that combines the introduction of windfarm friendly radar technology at RRH Trimingham, Staxton Wold and Brizlee Wood that has enabled >5GW windfarm development projects, which are equally important to the Department of Energy and Climate Change to meet its commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and the Ministry of Defence"

"8(a) Business Development Program[edit]

The 8(a) Business Development Program assists in the development of small businesses owned and operated by individuals who are socially and economically disadvantaged, such as women and minorities. The following ethnic groups are classified as eligible: Black Americans; Hispanic Americans; Native Americans (American Indians, Eskimos, Aleuts, or Native Hawaiians); Asian Pacific Americans (persons with origins from Burma, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Brunei, Japan, China (including Hong Kong), Taiwan, Laos, Cambodia (Kampuchea), Vietnam, Korea, The Philippines, U.S. Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (Republic of Palau), Republic of the Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Samoa, Macao, Fiji, Tonga, Kiribati, Tuvalu, or Nauru); Subcontinent Asian Americans (persons with origins from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, the Maldives Islands or Nepal). In 2011, the SBA, along with the FBI and the IRS, uncovered a massive scheme to defraud this program. Civilian employees of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, working in concert with an employee of Alaska Native Corporation Eyak Technology LLC allegedly submitted fraudulent bills to the program, totaling over 20 million dollars, and kept the money for their own use.[26] It also alleged that the group planned to steer a further 780 million dollars towards their favored contractor.[27]"

Yours sincerely,

Field McConnell, United States Naval Academy, 1971; Forensic Economist; 30 year airline and 22 year military pilot; 23,000 hours of safety; Tel: 715 307 8222

David Hawkins Tel: 604 542-0891 Forensic Economist; former leader of oil-well blow-out teams; now sponsors Grand Juries in CSI Crime and Safety Investigation

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.