Investigation of the Death of a United States Marine Corps Colonel

Bryan R. Burnett, M.S.1 and John David Sabow, M.D.2

Introduction

A United States Marine Corps colonel died between 0835 and 0900 on January 22, 1991. The death occurred in the backyard of his home on the El Toro MCAS, Orange County, California.

Figure 1. Photographs from the death scene. A: The body in the backyard of his home. The shotgun is in front of him with his legs over the shotgun stock. A patio chair is on top of the body. The bathrobe is tucked between his legs to the crotch. B: Another view of the body. C: View of the victim's legs and feet with the shotgun stock underneath. D: View of the body from the rear. The bathrobe was tucked between the legs to the buttocks.

The colonel was found lying on his right side dressed in a white terrycloth bathrobe, white undershirt, light blue pajama bottom, white socks and black slippers (Fig. 1). The death certificate, issued the next day, stated he had died by suicide. Death was alleged to be by an intraoral shotgun discharge. The close proximity of the victim's shotgun (Ithaca 12 gauge double barrel shotgun) to his body as well as a patio chair on top of him support a suicide scenario. However, bloodstains away from the body, the autopsy report images, X-rays and the autopsy and death scene photographs indicate homicide. This report will examine the evidence and the 1 Meixa Tech, P.O.Box 844, Cardiff, CA 92007. brburnett@meixatech.com 2 Board Certified Neurologist and Practicing Forensic Neurologist, P.O.Box 5510, Rapid City, SD 57709. doctorman1@aol.com reconstruct the events leading to the death of the colonel.

In 2003 Congressman Duncan Hunter, Chairman of the Armed Services Committee, was apprised of the controversy regarding the colonel's death. In response, Congressman Hunter amended the United States Defense Authorization Bill for 2004 to include instruction to the Department of Defense for a reinvestigation of the death. The Department of Defense chose Jon Nordby to conduct the mandated investigation which resulted in a report (Nordby, 2004) submitted to the Department of Defense and the Congress.

Figure 2. The death scene drawn to scale using the measurements provided by the Naval Investigative Service (NIS, 1991) on the scene drawing. The body graphic is the one originally rendered in the scene drawing, but sized and rotated to the scaled position. The grass bloodstain positions G and H were adjusted according to those measurements on the scene drawing and their positions are shown in relation to the body. Color was added by authors. The scene is portraying the suicide scenario. The estimated original position of the patio chair (red square) in the suicide scenario is based on the shotgun pivoting on its stock to the location under the victim's legs and feet, as shown with the colonel being "propelled" by the shotgun blast backward and to his right. He somehow straightens his body.

The 2004 Nordby report, which concluded suicide, was not convincing to us. We conducted an independent study which resulted in a report to Congressman Duncan Hunter (Burnett and Sabow, 2007). We concluded the colonel died by homicide. The gunshot residue (GSR), backspatter residue (BSR), bloodstain examination and crime scene observations of that report are presented here. The death scene drawing (Fig. 2) illustrates the suicide interpretation of the colonel’s death.

Figure 3. A. Reenactment of the suicide scenario with the victim sitting in a chair and inserting the shotgun into his mouth. The muzzle is gripped by the left hand while the right hand is at the trigger. The shotgun was found under the right leg (Fig. 1). This would place the shotgun in the reenactment on the outside of the right leg. In this scenario, gas escape from the mouth would spray the thighs (red arrows) with GSR, BSR and blood/tissue on the front of the bathrobe and/or the thighs of the pajama bottom. The red dashed line on the lower right leg outlines the probable area of GSR deposition if there were breech and trigger housing gas leakage by the shotgun. B. Reenactment of part of the homicide scenario where the shotgun is inserted into the mouth of the victim by an assailant. In order for the muzzle to remain in the mouth when the shotgun is fired, the stock of the shotgun would have to be supported. Evidence for a rapid exit (recoil) of the muzzle of the shotgun in this scenario is the rotation and drop to the grass of the left hand before receiving blowback blood (see text). The right hand was not exposed to detectable GSR. However, blood spatter is on the right hand which would also place this hand close to the nose and mouth, the only sources of blood shedding. The death scene photographs (Fig. 1) show the victim's right hand near the mouth. Red arrows: route of the gas expellation (early blowback) while the shotgun muzzle was in the colonel's mouth.

The two scenarios as to how the colonel died:

He committed suicide with his 12 gauge shotgun by sitting in a chair placing the shotgun in his mouth (Fig. 3A). The shotgun muzzle was held at his mouth with his left hand and he pushed the trigger with a finger or the thumb of his right hand. The position of the body (Figs. 1 and 2) suggests that consistent with this scenario, the shotgun was held outside his right3 leg and after the shot, he somehow fell backward from the chair and onto his right side causing the patio chair to upset and land on top of him (Fig. 2). This is the theory promulgated by Nordby (2004 and 2006).

He received a blow to the back of his head, which rendered a fatal injury. While the colonel was lying on the ground, the assailant inserted the victim's 12 gauge double barreled shotgun into his mouth and fired the left barrel. This part of the scenario is reenacted in Fig. 3B. The shotgun was positioned under the colonel's legs and a patio chair placed on the body (Fig. 1) in order to generate the appearance of suicide.The paper by Sabow and Burnett (2011) examined the pathology. Revealed in that study was evidence of a depressed right occipital skull fracture which was shown to have occurred prior to the intraoral shotgun discharge. The colonel had received a strong blow by a club to the back of his head prior to the intraoral shotgun blast. The study presented here examines the GSR and BSR by scanning electron microscopy, the bloodstains on and around the body and the positions of the body and clothing. A scene reconstruction is presented.

Gunshot and Back Spatter Residues

Particle types. Two general particle types involved in this case can be detected by scanning electron microscopy (SEM)/energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDS):

Gunshot residue (GSR). The particles that are produced by the firing of a gun are usually composed of lead, antimony and barium in various combinations. These particles originate from the primer of the cartridge. Other elements that are occasionally found associated with GSR, are aluminum, silicon, sulfur, chlorine, potassium, calcium and iron. In addition, bullet- origin particles composed of copper, zinc and nickel are also produced and are often associated with the primer-origin particles. Unjacketed bullet and some jacketed bullets will produce large amounts of lead particles (Wolten, et al., 1977) in GSR from both the breech and muzzle. For a shotgun, lead shot ablation coupled with heat would generate lead particles as they travel down the bore.Leakage of GSR-laden gases from the shotgun, if it occurs, would be from the breech area and perhaps the trigger housing of the Ithaca shotgun (Fig. 4). There appear to be no published reports on breech GSR leakage of side-by-side double barrel shotguns. Once it was established that the shotgun has breech leakage of GSR-laden gas, the major part of the particle burden study is the examination of samplers taken from the colonel's bathrobe and pajama bottom and4 examined by scanning electron microscopy/energy dispersive x-ray analysis (SEM/EDS).

Back spatter residue (BSR). These are particles produced by a contact or near contact shot to the head included in blowback. The interaction of the bullet, or in this case, lead shotgun pellets and hot gases with bone (calcium and phosphorus) will produce characteristic particles of lead-calcium-phosphorus and particles composed of bone (Burnett, 1991). Gunshot residue particles would also be associated with BSR.

Martinez (2000) notes, "...GSR can be readily detected and identified on clothing and in automobile interiors with the same simple sampling techniques as those used for collecting P- GSR [primer gunshot residue] from the hands. The results obtained proved to be a valuable investigative tool in reconstructing the possible events of firearms related crime and should not be overlooked by the forensic scientist." Unfortunately, this viewpoint is not universally accepted. Contrary opinions have been proffered by criminalists in case work. For instance, in the case California v. Robert Blake (2005, Los Angeles, California), a criminalist stated in a memo when asked to analyze sweatshirts for GSR, "...explain to [the detective] that gunshot residue particle analysis cannot prove or answer his question. Any interpretation of the presence or absence of gunshot residue on surfaces other than bare hands is unfounded and possibly misleading" (Burnett, 2005A). In the case of California v. Philip Spector (2007, Los Angeles, California), another criminalist did not sample Spector's jacket sleeves for GSR, even though Spector likely washed his hands prior to sampling. If one of Spector's hands had been in close proximity to the revolver when it discharged, his jacket sleeve would have had GSR deposited on it. Discovery of heavy GSR deposition on one of the jacket sleeves would have been inculpatory (Burnett, 2007). Long-term persistence of GSR on clothing is known (Mann and Espinoza, 1993) and according to some criminalists, it cannot be establish that the shooting at issue was that which deposited GSR. However, the history of an article of clothing as to recent launderings and the probability of exposure to GSR from another source should be evaluated for any item suspected of involvement in a shooting.

Figure 4. The shotgun. A: Full view of the Ithaca shotgun with the Winchester "Game Load" box and cartridges used in the test of the shotgun. B: The serial number of the shotgun. C: Identification information on the barrels of the shotgun. D: The trigger area of the shotgun. The trigger housing gap is indicated. E: The opened breech of the shotgun. F: The closed breech area of the shotgun.

Figure 5. Reenactment of the suicide scenario with a mannequin wearing the victim's clothes. A: Pink area: region where most of the back spatter in this scenario will hit the bathrobe. B: Close up of the mannequin's right leg with the shotgun in place. C: As in B, but the bathrobe is off the right leg. In this scenario, the pajama right leg in the calf area would receive the breech and trigger-housing GSR. However, the body at the scene indicated that the bathrobe fully covered the leg. D: Another variation of the suicide scenario with the shotgun between the legs. This scenario is unlikely for the reason described in C and the scene photographs show the shotgun was positioned outside the right leg.

Niemeyer (2000) described sampling and detection of GSR from the inside of a pocket where a recently fired pistol was secreted. There was no GSR detected on the sampler from the other pocket. Chavez, et al (1991) described the effect of washing GSR-contaminated clothing. Mann and Espinoza (1993) assessed contamination of bow hunter hands by jackets that were worn during rifle hunting.

The author (BRB) has had cases over the last twenty-five years where the assessment of GSR burden on clothing and other inanimate objects had litigation value.

Figure 6. Photograph from scene showing the left hand of the victim in the process of GSR sampling. The arrow points to the GSR sampler. This is a "concentration technique" sampler made for SEM analysis, but was not analyzed. Swabs were also taken (no image, but in the video recording of the scene processing) and analyzed by atomic absorption spectroscopy.

The suicide scenario would place the breech of the shotgun on the outside of the right leg (Fig. 5A) which would likely deposit GSR (if the shotgun's breech leaks) on either the bathrobe (Fig. 5B) or the pajama bottom (Fig. 5C). In addition, the victim in the suicide scenario would be leaning slightly forward in order to prop the shotgun's stock on the ground (Fig. 3A). In this position, blowback would occur within a second (Burnett, 1991) after the shotgun discharge and spray the front and lap areas of the bathrobe with GSR and BSR. Concentrations of GSR on the outside right leg and GSR and BSR on the front and lap of the bathrobe would be the hallmarks of suicide in this case.

In the homicide scenario (Fig. 3B), there would be no focal (heavy relative deposition) GSR deposited on the bathrobe since the shotgun breech would be away from the body and the blowback from the mouth would also be directed away from the body. However, wind transport of GSR (White and Gross, 1994) and BSR onto the bathrobe is possible. If deposition by wind did occur, there might be a pattern to the distribution of GSR on the bathrobe.

The GSR samplers taken from the hands of the colonel at the death scene. One of the two types of SEM/GSR samplers available at the time was used to sample the colonel's hands. These SEM/GSR samplers were the "concentration" type (Zeichner, et al., 1989) and one was photographed at the scene (Fig. 6) while sampling the colonel's left hand. These samplers were apparently not analyzed at the time of the evidence processing and this sampler type currently is no longer used in GSR sampling and analysis. Video documentation of the scene processing by NIS criminalists showed swabs were also taken for GSR analysis after the SEM sampler sampling. The swabs were analyzed by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS). The AAS analyses were performed at the California Department of Justice Laboratory in Riverside, California. The report (Anon., 1991) indicated that there were four swab samplers, two for each hand, back and palm.

Analysis for GSR and BSR. The GSR and BSR burdens associated with the bathrobe and perhaps the pajama bottom would differ depending on suicide or homicide of the colonel.

Analysis question one. Does the shotgun produce any GSR-laden gas leakage at the breech and from the trigger housing when fired? Before evaluating the second and third questions, there needs to be verification that the 12 gauge shotgun produces breech GSR when fired. There are two areas in the shotgun where gas-laden GSR might contaminate the shooter: through the trigger housing (Fig. 4D) and the breech (Fig. 4F) .

Analysis question two. With the confirmation that the shotgun has breech/trigger housing leakage, a suicide scenario (Fig. 3A) for the death of the colonel would be supported by the detection of a large relative amount of GSR on the bathrobe corresponding to the lateral right calf region (Figs. 5A and 5B) or the same region on the pajama leg (Fig. 5C). The shotgun placed between the legs (Fig. 5D) in this scenario is unlikely, but is the position hypothesized by Nordby (2006). The positions of the bathrobe on the body of the colonel and the shotgun (Fig. 1) suggest if this was a suicide, the shotgun would be lateral to the right side of the body at the time of discharge. Considering the position of the body and the shotgun, the simulations depicted in Figs. 3A and 5A are the most likely for the suicide scenario. Thus, GSR should have been deposited on the bathrobe corresponding to the dashed outlined area depicted in Fig. 3A and the same area in Fig. 5A. If the bathrobe was away from the pajama legs, a heavy GSR burden would be on outside right pajama leg (Fig. 5C). Are there such concentrations of GSR on the bathrobe or pajama bottom of the colonel?

Analysis question three. In the suicide scenario, the major exit for the gas in blowback is the sides of the mouth around the barrel of the shotgun and to lesser extent the nose. The exiting gases from the mouth and nose (red arrows, Fig. 3A) would be directed onto the front of the bathrobe and likely produce a heavy deposition of GSR and BSR on the thigh areas of the bathrobe (pink area of Fig. 5A) or the pajama bottom of the victim (if the bathrobe did not cover this area, as shown in Fig. 5C). In a homicide scenario, the exit of the gas from the mouth would be away from the body (Red arrows, Fig 3A). Do the thigh areas of the bathrobe or the pajama bottom lap areas have BSR and GSR burdens?

The shotgun tests. The left barrel of the Ithaca 12 gauge shotgun was used in all tests. The ammunition used in the shotgun at the time of the victim's death was unavailable. Similar ammunition was obtained for the tests: Winchester "Game Loads" 12 gauge, 2 3⁄4 inches, 3 1⁄4 Dr. Eq., 1 oz., 7 1⁄2 lead shot. Lot Number, 47Y2UT22 (purchased January, 2005) (shown in Fig. 4A).

The SEM samplers used for sampling all the items in this examination were made of 13 mm diameter aluminum platforms upon which 1.5 mm thick graphite disks were affixed. On the graphite disk, a graphite-impregnated double-sticky tape was applied. The sticky surface of the sampler was dabbed onto the evidence item. The sampler was placed directly into the specimen chamber of the scanning electron microscope where it was viewed and analyzed. Some of the samplers were carbon coated. Two scanning electron microscopes were used in this study. For the non-automated analyses, an ETEC Autoscan scanning electron microscope was used with a Kevex thin-window EDS detector. The automated analyses were performed in the laboratory of Dr. Jozef Lebiedzik (Advanced Research Instruments Corporation, Golden, CO, USA).

Shotgun breech/trigger housing leakage. The first test of the shotgun was to determine if the breech and the trigger housing leaks GSR. A series of tests to detect breech and trigger leakage of the Ithaca shotgun were performed. The leaking of gunshot residue from both the breech and trigger housing during the firing of the Ithaca shotgun was confirmed in two of those tests. The third test series was to determine if GSR deposition of the shooting hand varied (i.e., directional deposition) with an oblique finger or thumb depression of the trigger (as would occur if this were a suicide, Fig. 3A).

The exterior of the shotgun was thoroughly cleaned. Following the cleaning, the shotgun breech was wrapped by a cotton cloth. The cotton breech wrap (sample I-1) was removed immediately prior to the wrapping of the breech test cloth (sample J-1) at the range. Other control samples were taken as described below.

No firearms were discharged at the indoor range for twelve hours prior to this test. The shooter wore a DuraClean® polyester glove. Only one shot was fired. Summary of the samples (60 dabs/sample).

I-1: Control cotton wrap of the shotgun breech prior to the final breech wrap (sample J-1).Table 1. Results of the testing of the breech and trigger housing of the shotgun. "GSR" includes particles of all elemental compositions of GSR, including lead-only particles. Twenty fields at 300X were counted per sample.

I-2: A polyester DuraClean® polyester glove that was put on the shooter's right hand prior to entering the shooting range building. The glove was carefully removed and stored just prior to putting on the test glove, J-3.

I-3: A cotton witness cloth, 20 X 20 cm exposed on the back bench of the range (approximately 5 feet from the shooting stall). Five minutes after the shot, this cloth was folded and placed in a sample bag.

I-4: A cotton cloth (8 X 20 cm) that was taken out of its plastic bag at the range, exposed on the back bench for approximately 3 minutes prior to the shot and then refolded and placed back in its plastic bag.

I-5. A cotton cloth (8 X 20 cm) placed on the shooting platform, under and to the left of the shotgun. prior to the shot. The distance of the breech/trigger of the shotgun when fired was approximately 50 cm from the center of the cloth surface. The cloth was folded and placed in a plastic bag immediately after the shot.

J-1: A cotton cloth wrapped around the breech of the shotgun to intercept GSR generated by breech leakage.

J-2: Control sampler, which was dabbed on J-3 DuraClean® polyester glove a minute prior to the shotgun discharge.

J-3: The DuraClean® polyester glove worn on the trigger hand after the firing of the shotgun.

It was apparent from the results of the analysis of the samplers that GSR-laden gas emanates from the breech and trigger housing (Table 1). In normal firing of the shotgun, the forefinger would be entirely across the trigger (Fig. 3B). But in the suicide scenario, the finger or thumb would approach the trigger obliquely (Fig. 3A) and there might be only partial exposure to the GSR laden gases from the breech area of the shotgun. Could the lack of detected GSR on the right hand be due to a non-uniform release of GSR-laden gas from the trigger housing?

In the final test of this series, two persons were required: one to hold the shotgun and the other to depress the trigger. Just after placing the polyester glove on the shooter’s hand (only the wrist edges of the glove were handled), 60 dabs of the glove surface were taken with the sampler. The ventilation system of the range was not working. The glove was quickly collected after each shot (turned inside out from the wrist during the removal) and placed in a plastic bag for later sampling. Three samples were taken from hands where the trigger was depressed obliquely:

N-1: Sixty control dabs of the glove while on the hand of the shooter at the range. N-2: A forefinger from the left side of the shotgun to depress the trigger (Fig. 5B).Items N-2, P-2 and Q-2 were sampled in the laboratory, 60 dabs per item.

P-1: Same as sampler N-1

P-2: A thumb from the left side of the shotgun to depress the trigger (Fig. 5C) Q-1: Same as sampler N-1

Q-2: A thumb from the right side of the shotgun to depress the trigger (Fig. 5D).

The results of those analyses indicate that regardless of the position of the hand and fingers in the depression of the trigger, GSR deposition occurs upon firing the shotgun. The data for this experiment series are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Results of the SEM/EDS analysis from the sample of the oblique trigger depress experiments; the controls showed a burden of GSR due to a failed ventilation system of the indoor range. Despite this contamination problem, the tested gloves were sufficiently populated with additional GSR to indicate that regardless of how the trigger was pressed, the hand that depressed the trigger would become populated with GSR. "GSR" includes all elemental compositions of GSR, including lead-only particles. Twenty fields at 300X were counted per sample.

The DCI Forensic Laboratory of South Dakota tested the Ithaca shotgun in the position as depicted in the suicide scenario (i.e., the muzzle directed up, as shown in Figs. 3B and 5A). The Winchester "Game Load" was the test ammunition. This was done at an outdoor range. A clean cloth glove was used for each test, in which the trigger was depressed by the normal position and four tests were made by oblique pressing of the trigger with either the forefinger or thumb of the right hand. The report (Maritz, 2006) for these tests noted a wind speed of approximately 12 MPH during the tests. The samples were analyzed at the RJLee Group’s laboratory in Pennsylvania. These data are presented in Tables 4 and 5.

Sampling and testing of the bathrobe and pajama bottom for GSR. The samplings of the bathrobe utilized GSR samplers as noted above. Nine GSR samplers, K-1 through K-9 were applied, 60 dabs per sampler per region of the bathrobe (Fig. 7A). Nine GSR samplers, H-1 through H-9 were applied, 60 dabs per region, on the pajama bottom (Figs.7B and 7C).

The samplers were examined by automated SEM at 180X at the laboratory of Dr. Jozef Lebiedzik. As much as 40% of each sampler surface was scanned.

Table 3. Results of the SEM/EDS analyses from the samplers of the gloves taken by the DCI Forensic Laboratory and analyze the RJLee Group, Inc. (Schwoeble. et al. 2006). Overall these data confirm those of this study (Table 2). However, the low numbers of reported GSR particles are likely due to a wind of 12 MPH at the range (White and Gross. 1994) that prevented much of the GSR deposition on the cloth gloves.

Figure 7. SEM sampler series H and K. Sixty dabs per sample. A: Sample regions of the bathrobe (samples K-1 through K-9). B: The front areas of the pajama bottom (Samples H-1 through H-6). C: The back of the pajama bottom showing the SEM tape lift area H-7 (buttocks), H-8 (left rear thigh) and H-9 (right rear thigh).

A second series of analyses of the K samplers, independent of the first series was performed by Dr. Lebiedzik. During the first analyses of the K samples, he noted that cotton fibers picked up along with the inorganic particles were charging. This caused electron beam deflection and particles were likely missed. The K samplers were carbon coated and six of these samplers reanalyzed. Included in the second series of analyses are assessments of calcium-phosphorus (CaP - bone), lead-phosphorus (PbP - the geochemical end-point for soil lead) and lead- phosphorus-calcium (PbP Ca - bullet/shot lead + bone). The latter particle type, is a characteristic product of contact/near contact gunshot to a head that is found in the resultant back spatter (Burnett, 1991).

Results and discussion of the GSR and BSR tests.

Gunshot residue samples of the victim's hands at the scene. Gunshot residue sampling of the victim’s hands was performed at the scene. It was apparent from the GSR report (Anon., 1991) that atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) was used to analyze these samples. A major criticism of the AAS technique, which ultimately led to it to no longer being used for GSR analysis by crime laboratories for this application, is that elemental associations cannot be determined and automated SEM/EDS is more sensitive (Romolo and Margot, 2001). A video taken during the scene processing showed the criminalist, after dabbing the victim’s hands with concentration-technique GSR samplers, swabbed the same hand areas with cotton-tipped applicators. It was these applicators that were analyzed by AAS for GSR metals. The reliability of this sampling procedure (SEM dabbing followed by swabbing) for the swab-AAS testing has never been tested. It is possible the right hand had been contaminated with GSR, but the dabbing with the GSR SEM samplers prior to the swabbing had removed most of the GSR so that none was detected on the right hand. The soot areas on the left hand were sampled by both sampler types.

In both the suicide scenario (Fig. 3A) and homicide scenario (Fig. 3B) show the right hand’s probable exposure to GSR: the suicide scenario by breech GSR and homicide scenario by early blowback.

Figure 8. Gunshot soot (arrows) on the left hand of the colonel; photographs taken at the scene. The tip of the index finger shows a patterned bloodstain (circle).

The results from the report (Anon., 1991):

"The gunshot residue collection kit from Sabow was analyzed for the elements antimony and lead by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. These elements can be found in gunshot residues. Very high levels of antimony and lead were found on the palm and back of the left hand samples, while samples from the right hand were negative. This could be due to the left hand being near the muzzle of the discharging shotgun."The AAS data were not presented in the report and the author's name had been removed from the copy reviewed.

Breech and trigger-housing leakage. The shotgun has breech and trigger-housing leakage. This was determined in this study (Tables 1 and 2) and the tests performed by the DCI Forensic Laboratory and analyzed by the RJLee Group (Schwoeble, et al., 2006; Table 3).

The data presented in Table 3 provide numbers substantially less than those found in the present study (Table 2). It is apparent that a wind of 12 MPH (Maritz, 2006) at the range prevented deposition of much of the GSR (White and Gross, 1995) produced by the breech and trigger housing upon the firing of the 12 gauge shotgun.

Regardless of the wind issue, it is probable that objects such as the bathrobe or pajama bottom and the hand of the shooter; either the victim (in the suicide scenario) or assailant (homicide scenario) near or in contact with the Ithaca shotgun breech and trigger areas will be contaminated with GSR.

No wind was recorded for El Toro area on January 22, 1991 until 1000 (Weather Underground, 1991). This is confirmed by the leaves on the lawn remaining stationary at the scene throughout the photography period.

The nature of close-range shots to heads. The evidence presented in this case shows two distinct events occurred with the intraoral shotgun discharge. DiMaio (1999: Figure 5.4, p. 129) notes with a contact or near contact to a head that there is often a dissection (gas-filled void) between the scalp and the skull. This is followed by collapse of this space which results in initial blowback. But, in this case the shotgun blast was intraoral. The oral cavity is analogous to the temporary cavitation described by DiMaio. There is likely little difference between intraoral and scalp/skull early blowback and early intraoral blowback, except the former might have more tissue components involved in the blowback.

Table 4. Results of the automated SEM/EDS analysis of the samples from the bathrobe (K samples) and the pajama bottom (H samples); samples analyzed by Dr. Jozef Lebiedzik. "#" = number of particles; "EST" = number particles estimated on the entire sampler surface.

Table 5. Results of the second analysis series performed by Dr. Lebiedzik for six of the K samples from the bathrobe is shown; along with the second analysis series, calcium- phosphorus (CaP), lead-phosphorus (PbP) and lead-phosphorus-calcium (PbP Ca) burden were assessed. See text for additional information. "#" = number of particles; "EST" = number particles estimated on the entire sampler surface.

The second event is an "exhalation" of the gas that was injected into the skull by the gunshot, which follows and transitions from the initial or early blowback. This is likely especially true when there is no exit wound (Burnett, 1991). More organic debris (blood and other tissue) is associated with the second event in this case than the first. The present study shows that the intraoral 12 gauge shotgun blast without an exit wound presents the early blowback phase that is mostly made up of soot and GSR (Fig. 8 and see below). This transitions into a second phase blowback of gas with blood, other tissue debris, BSR and GSR. Evidence for this two-phase blowback from the victim will be discussed blow.

The bathrobe and pajama bottom. The results of the analyses presented here and by the RJLee Group (Schwoeble et al., 2006) indicate that the shotgun leaks GSR when fired.

The results of the analyses by Dr. Jozef Lebiedzik of the eighteen tape lifts from the bathrobe and pajama bottom are presented in Table 4. For the bathrobe (the K samples) only two characteristic (PbSbBa) particles were detected (Table 4). The lead-only particles represent a significant problem in GSR interpretation due to many possible environmental sources, including piston-engine aircraft exhaust (the colonel's house was in the flight path of the El Toro MCAS runway). So, the levels of "lead-only" particles found associated with the bathrobe cannot be attributed solely or even partly to the shotgun blast unless those levels are compared with samplers of articles of clothing that could not have been exposed to GSR.

The calcium-phosphorus (actually calcium phosphate) or bone particles on the bathrobe (Table 3) may be from blowback. But ground bone, "bone meal," is used as a fertilizer additive. The association of lead with calcium phosphorus would have been created by the blowback event. The lack of lead-associated calcium-phosphorus particles indicates the calcium phosphorus particles identified in these analyses are from an environmental source.

The lead-phosphorus particles have a quite different origin. These particles are the endpoint of the geochemical transition of soil lead (Cao et al., 2003). The presence of lead-phosphorus particles on the bathrobe indicate these and other lead-bearing particles, without antimony or barium association, have an environmental source.

The estimated GSR burdens from the pajama bottom samplers are different from the bathrobe (Table 4). These samplers document an exposure to GSR of the pajama bottom the bathrobe did not receive. The two-component GSR (lead-antimony and lead-barium) particles are generally present on the pajama bottom, but only one particle of this type was found on the bathrobe. There are also more of the characteristic (PbSbBa) particles on the pajama bottom than on the bathrobe. The lead-only particle burden of the pajama bottom is also large compared to the bathrobe. The assumption in the comparison of the GSR burdens of these two articles of clothing is that both have nearly identical exposure histories prior to the shotgun blast and the pajama bottom was not contaminated by the other clothing items (underwear and t-shirt) that shared the same storage container.

The suicide scenario shotgun position (Fig. 3A) proposes that the colonel fell back and to his right off the patio chair following the intraoral shotgun blast (Nordby, 2004 and 2006). During the fall from the patio chair, the shotgun pulled from his mouth and the stock ended up beneath his legs and feet. He somehow straighten his body. The body position will be discussed in more detail below. The position of the shotgun in relation to the body suggests it was against the right leg as shown in Fig. 3A at its firing. The scene photographs also show the victim’s bathrobe tucked between his legs (Fig. 1A and see below). Thus, for the suicide scenario, the bathrobe would have to be covering the colonel’s legs and intercept the GSR from both the breech and the trigger housing at region K-9 (Fig. 7A).

In the suicide scenario, with the bathrobe covering the victim's legs to its full extent as shown in the scene photographs, (Figs. 1 A and 1B), at least the areas K-6 and K-7 (Fig. 7A) should have evidence of extensive contamination by blowback (back spatter) of both GSR and BSR. No particle burdens supportive of this event were observed.

The GSR evidence of the bathrobe and the pajama bottom show:

1). The bathrobe was not in a position to become contaminated with GSR and BSR when the shotgun was discharged. The GSR contamination of the pajama bottom versus the bathrobe, means that the bathrobe was shielded from GSR contamination. The bathrobe was likely partly folded, turned inside out and "hiked up" on the victim so that the bathrobe was not contaminated with GSR when the shotgun was fired. The bathrobe likely covered little, if any, of the pajama bottom when the intraoral shotgun blast occurred.In the suicide scenario, the thighs of the bathrobe or perhaps the pajama bottom would be heavily contaminated with GSR and BSR, which was not the case for either item.

2). The pajama bottom, because of the lack of cover by the bathrobe, was contaminated with GSR particles (Table 4). Curiously, one of the heaviest GSR contaminations was the buttocks region (sample H-7, Fig. 7C) of the pajama. This may have occurred due to the GSR-laden cloud from the shotgun blast drifting over the lower abdomen area or contact was made by the GSR-contaminated assailant (homicide scenario). The pajama covering the lower abdomen was not sampled. Regions H-4, H-5 and H-6 (Fig. 7B) also had relatively heavy GSR contamination. These three regions of the pajama bottom were apparently also exposed to the shotgun-produced GSR cloud when it discharged from the colonel's mouth and/or the shotgun's trigger housing and breech. With the victim lying on his right side in the homicide scenario, regions H-1 and H-3 would receive less surface exposure to GSR contamination. Indeed, these areas show less contamination than H-5, H-6 and H-7. The back of the thighs of the pajama bottom (H-8 and H-9) were shielded from the GSR source and received the least contamination. Alternatively, the pajama became contaminated in the areas that contain GSR particles when the shooter, with GSR-contaminated hands, participated in the staging of the body.

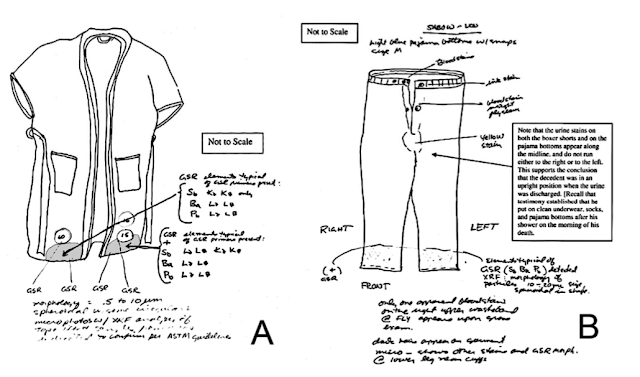

However, Nordby presented a report (2006) to the United States Department of Defense and Congressman Duncan Hunter, Chairman of the Armed Services Committee in 2006 which refutes the first report on GSR in this case (Burnett, 2005B) and the conclusion the colonel was murdered. Gunshot residue burdens without support data or images from of the colonel's clothing were briefly discussed in two of the pages from Nordby (2006) which include the hand- drawn and written figures shown in Fig. 9. Nordby apparently used x-ray fluorescence ("XRF," in the handwritten notes, Figs. 9A and 9B) to detect lead, antimony and barium. He reports observing 0.5 to 10 micron diameter GSR particles, which must have been by SEM/EDS. Of Nordby's 285- page report, only the first 28 pages were available despite a number of requests for the entire document.

Figure 9. Drawings and handwritten notes showing the results of Nordby's GSR testing of the bathrobe and pajama bottom (from Nordby, 2006). Portions of the figures are illegible in the source. A: Nordby's drawing of the bathrobe where he indicates he had found GSR concentrated along the lower front hem (shaded area). The lower margins of the bathrobe were enhanced by adding gray to the areas originally shaded, but lost in the copying. B: A similar drawing of the pajama bottom; a concentration of GSR was discovered by Nordby on the front cuffs of the pajama pants.

Nordby (2006) attributes his finding of GSR on the bathrobe lower hem and pajama bottom cuffs to the discharge of the shotgun between the colonel’s legs (Fig. 5D) rather than on the lateral side of the right leg (Figs. 3A, 5A and 5B) as would be indicated by the position of the shotgun with the body (Fig. 1) in the suicide scenario. However, his conclusion is consistent not with the suicide scenario, but with the homicide scenario where the assailant shooter handled the bathrobe and pajama bottom at these locations while staging the body (see below). If the shotgun breech was positioned near either the bathrobe or pajama bottom between the colonel's legs (Fig. 5D) as suggested by Nordby, GSR should have been detected in areas H-5 and H-6 of the pajama bottom (Fig. 6B, Table 4). Although GSR from pajama bottom region H-6 was detected (Table 4), it is not in sufficient quantity to have been deposited by the closely-associated Ithaca shotgun breech.

Figure 5D shows just how untenable Nordby's suicide scenario is with the shotgun placed between the colonel's legs:

1. The bathrobe's lower hem (Fig. 9A) simply would not be exposed to the shotgun breech (Fig. 5D) since it would be impossible for the bathrobe to cover the inner legs as would be necessary to be exposed to the shogun's breech discharge.The sampling described in our study was apparently above those GSR deposits found by Nordby. The only way for Nordby's GSR deposits (Fig. 9) to have occurred and be consistent with the results presented in Tables 4 and 5 is for the GSR-contaminated shooter participating in the staging of the colonel's body.

2. The shotgun's breech is too high on the pajama pant legs in the suicide scenario (Fig. 5D) to have deposited GSR at the locations shown in Fig. 9B.

The positions of the left and right hands at the shotgun blast. In both scenarios presented, the left hand gripped the barrel near the muzzle at the victim's mouth when it fired. In the suicide scenario, the colonel gripped the shotgun himself in the manner shown in Fig. 3A. In the homicide scenario, the victim's left hand was held in the same position on the shotgun's muzzle by the assailant as shown in Fig. 3B. The presence of soot on the left hand (Fig. 8, arrows) means a heavy burden of muzzle GSR was deposited on the left hand when the shotgun fired. Indeed, GSR was reported present on the left hand (Anon., 1991). The shotgun muzzle remained long enough in the victim's mouth that "minute amounts of tissue blowback within the barrels" (NIS, 1991) were observed.

In the suicide scenario (Fig.3A), the right hand would be exposed to breech, not muzzle GSR.

In the homicide simulation the left hand was lifted off the ground so that the right hand would receive muzzle GSR in early blowback (Fig. 3B). Early blowback occurred through the sides of the mouth when the shotgun was momentarily present (recoil pulled the shotgun muzzle out of the mouth) and before the left hand dropped to the ground which was when the right hand was exposed to GSR. The left palm also likely received soot and GSR which was subsequently covered by blood-laden blowback when the left hand returned to the ground.

Therefore, the right hand would be exposed to GSR contamination in both the suicide and homicide scenarios. No GSR was detected on the right hand, which was likely due to a flawed sampling procedure and low sensitivity of AAS compared to sampling for and analysis by SEM/EDS.

Bloodstains

The bloodstains in the grass - Stains G and H. Mentioned previously and illustrated in the scene drawing (Fig. 2) are the bloodstains G and H in the lawn near the Colonel's body. A number of first-generation (i.e., prints directly from the negatives) scene photographs were made available to this study include the location of these two stains, but with all, except one, close examinations and image enhancements, the alleged bloodstains could not be identified. The two scene photographs of a criminalist pointing to the stains (e.g., Fig. 10A of stain G), proved impossible to discern the alleged stains for these images. These stains could occur with expirated blood, which was verified by one exceptional image (Fig. 10B, arrows) where, with global enhancement in Photoshop, blood spatter can be seen which is consistent with expiration blood (James et al., 2005) on the grass blades.

The bloodstains in the grass - Stain under and in front of victim's head. The large bloodstain under and in front of the colonel's head was examined. The high resolution of these photographs played an important part in the analysis of this bloodstain. By enlarging areas of the grass around the head with images both before and after the body was turned over on its back it is possible to position the head and left hand in relation to the bloodstain (Fig. 11A). The positioning of the left hand in relation to the stain indicates this hand acted as a barrier for the bloodstain (Fig. 11B). In the gap between the left and right hand (Fig. 11B), there is no evidence of blood. The bloodstain itself (Fig. 11C) can be divided into regions (Fig 11D) according to origin. At the 3 o'clock margin of this stain the bathrobe on the victim's shoulder absorbed mostly serum from this stain ( "BATHROBE WICKING", Fig. 11D).

Figure 10. Scene images of the area of grass bloodstain G. A: The criminalist's pen can be seen in this photograph of the area of stain G. B: The stain is made up of small droplets of blood (arrows) that can be discerned on the blades of grass. The origin of this blood is expirated which was deposited prior to the intraoral shotgun blast. Both images globally enhanced with Photoshop.

This stain is composed mostly of blood that emanated from the mouth and nose. The blood had coagulated in the central part of the bloodstain on the left palm. The lower part of the stain in the image ("BLOWBACK (MOUTH)", Fig. 11D), although also emanating from the mouth was created by the bloody blowback from the intraoral shotgun blast. Figure 11E, is an enlargement from the scene photograph of part of that stain. The blood on the grass blades has a mosaic coverage. If this stain had its origin as the adjoining stain, i.e., flowing blood from the mouth and nose, the bloodstain would be solid and continuous. The blowback bloodstain will be discussed in more detail below.

Figure 11. Analysis of the bloodstain in the grass under and in front of the head of the victim. A: The bloodstain showing where the forehead, nose and left hand " forefinger" were in relation to the stain. The position of the head over the stain was estimated comparing features of the grass and leaves (there was little or no wind during the scene processing)in the photographs before and after the body was turned over. B: The hands of the victim. The left hand blocked the blowblack in that no bloodstain is apparent between the left and right hands. C: From the same photograph as A, but enlarge and Photoshop globally enhanced to show the distribution of the types of bloodstains. D: Map of the bloodstain showing the likely origin of the regions of the stain (See text). Red rectangle: the region shown in E. E: Region of the back spatter part of this bloodstain showing mosaic bloodstaining on the grass (arrows).

The left hand and arm. There are a variety of different bloodstains on the left arm and hand (Fig. 12).

The region on the radial wrist shows a splotchy bloodstain with an irregular margin (Fig. 12A, "EXPRIATED BLOOD" and Fig. 11B). The radial side of the forearm was not in contact with any obstructing surface as indicated by the irregular margin of the bloodstain. This is in contrast to the ulnar side of the wrist where the bloodstain has nearly a linear margin. The bloodstain on the ulnar side was limited by the flexor carpi radialis tendon which indicates that the ulnar forearm was rotated away from the mouth when the bloodstain was deposited. This blood was deposited by a "spray" so that overall it is a thin coating. Bubbles are seen throughout the stain as well as streak-like features that resemble mucus mixed with blood (Fig. 12B). This stain is from expirated blood.

Figure 12. A: The bloodstains of the left hand and arm. The pink arrows indicate the direction from which the stain was deposited. The blood droplets at the green arrows originated either from expirated or projected blood from blowback. Circle: the forefinger tip was shielded by the thumb. Inset: The forefinger in a more ventral view revealing a shielding by finger three occurred. These images show that the blood on the palm and dorsal distal fingers originated while directly in front of the mouth, i.e., from the bloody blowback event. Bloody blowback was directed into the palm as indicated by the larger pink arrow. Scale at the lower right corner of the image was made at the wrist and was derived from a simulation scaling. B: Enlargement of the expirated bloodstain on the wrist. Bubbles and apparent mucus involvement can be seen throughout the stain. C: Bloodstain smear (arrow) that was caused by the victim's right ulnar palm due to postmortem manipulation of the body. The circular dark bloodstain (above the arrow) is the dried margin of a portion of the blowback bloodstain.

The left hand of the victim also has a thick bloodstain that covers the entire palm area as well as most of the distal dorsal fingers (Fig. 12C). The origin of this bloodstain is indicated by the patterned bloodstain on the forefinger (Figs. 8 (circle), 12A (Circle) and 12A(inset)) and the palm bloodstain itself. The forefinger was shielded by the thumb and finger three of projected blood from the mouth and occurred by the left hand being directly in line with the bloody blowback. This stain is the back spatter from the bloody blowback event. In addition, the blood on the lateral portion of the ventral palm is smeared (Fig. 12C) where the smear is directed proximally from the palm to the distal (ulnar) margin of the wrist. The transfer occurred when the blood on the palm had partially dried.

Two bloodstains on the left arm just proximal to the expirated stain (Fig. 12A, green arrows) both have spines and satellite spatter that indicate a proximal directional vector of deposition on the ventral arm (Fig. 12A, smaller pink arrows). These two stains originated from the mouth either during the bloody expiration period or as part of the bloody blowback.

Figure 13. The right hand of the victim from death scene photographs. All of the images are enhanced. A: The two types of bloodstains are shown. The red arrows point to blood spatter. B: The two types of bloodstains are shown. The red arrows point to projected spatter. Blood spatter on the nail of the fourth finger is clearly visible; green arrows point to thin transfer bloodstains on fingers 4 and 5. C: The entire transfer bloodstain on the back of the hand is shown (image enhanced by Photoshop).

The right hand. Images of the victim's right hand from three different scene photographs are shown in Fig. 13. These photographs show two types of bloodstains: projected blood spatter and transferred. The right palm and the nail of finger four show small blood spatters (Figs. 13A and 13B, arrows). Because of the small size and location of these bloodstains, they were generated either during the period of blood expiration or the by the bloody blowback.

The ulnar aspect of the right palm, extending around to the back of the hand, is a blood transfer (Figs. 13A, 13B and shown in its entirety in Fig. 13C). The size and shape of this stain indicate24 it is a transfer from the left hand palm that occurred after the blowback blood went into the palm and dorsal fingers of the left hand. The solid part of this right palm stain is at the back of the hand with the streaks toward the palm.

If the right hand depressed the trigger in the suicide scenario, its palm would be turned away from the mouth (see Figs. 2B, 5A, 5B and 5C), and not be exposed to intercept blood spatter.

Figure 14. A: Bloodstain/spatter on the left side of the face. B: Blood smearing (likely a transfer) and two spatter drops on the chin (origins at arrows). The flow of blood from the chin toward the mouth is consistent with the victim's head as originally found and with the shotgun blast delivered when the victim was on the ground (Fig. 1). C: Enlargement of a scene photograph showing the reflected blood blowback on the anterior left pinna of the victim which flowed toward the top of the head. This is again consistent with the victim's head as originally found and with the shotgun blast delivered when the victim was on the ground (Fig. 1).

The face and bathrobe. There are a number of bloodstains on the face of the colonel, most of which are around the nose and the mouth (Figs. 14A and 14B). These stains appear to have been deposited by transfer from the lateral part of the left hand (no images available). There are two blood drops on the chin of the victim (Fig. 14B, arrows) that had flowed toward the mouth after impact. The origins of these blood flows are indicated by arrows. The flow of the blood is toward the mouth and is consistent with the found position of the body and not consistent in the suicide scenario, where in the suicide scenario these blood drops should have flowed in the opposite direction, while the victim was sitting (Fig. 3A) and then changed direction to correspond to the final position of the body (Fig. 1). A small blood drop hit the anterior left pinna (Fig. 14C) and flowed anteriorly in concordance with the position of the body, also without a change in direction.

There are small bloodstains on the chest area of the bathrobe (Fig. 15A) and a blood spatter on the left sleeve (Fig. 15B) as well as one other in the right arm which was mentioned in the video, but not recorded by a photograph available to this study.

The bathrobe – wicked bloodstain. The bathrobe that was in contact with the large bloodstain in front of the face, absorbed blood serum in a wicking manner (Fig. 15C).

Figure 15. A and B: Blood spatter on the bathrobe at arrows that likely occurred as splash-back on the left hand from the blowback event. C: The bloodstain on the bathrobe shoulder. There was little, if any, direct blood deposition from the source (the mouth and nose). The stain appears to be mostly serum that was wicked from the large bloodstain under and in front of the victim's head.

Discussion of the blood evidence

Ear bleeding and expirated blood. The blow to the head not only caused the depressed skull fracture but a severe basilar skull fracture (Sabow and Burnett, 2011). It was the basilar skull fracture that lacerated the mucosa of the nasopharynx (Singhania, 1991) and was the major blood source in the aspiration and expiration of blood. Blood from a basilar skull fracture often invades the middle ear and if severe enough, there is bleeding from the ear canal (Wyngaarden and Smith, 1985), as happened in this case.

Bloodstains G and H. Bloodstains G and H are consistent with the homicide scenario where the colonel was first struck with a club and fell to the ground lying on his right side. In extremis, he exhibited brainstem seizures (decerebrate and decorticate postures—see Posner, et al., 2007) and hyperventilation during which time he forcefully expirated and inhaled blood into the right lung (Feldman, 1994) resulting in this lung accumulating a large amount of blood (Singhania, 1991). The grass stains labeled G and H are small blood droplets on the grass blades of the grass (Fig. 10B) that resulted from the expiration of blood. These stains also indicate the colonel's body/head had repositioned at least twice prior to the final body position shown in the scene images. For the suicide scenario, G and H would have had to result from blowback because expiration would be impossible without a brainstem (Posner, et al. 2007). In the suicide scenario (Fig. 3A), the colonel would be sitting at least four feet distant from these bloodstains. These bloodstains would have been more massive if they were the result of projection by blowback in the suicide scenario.

Figure 16. Positions of the hands at the scene. The left hand has nearly the same position that it had at the major blowback event. However, both the thumb and the forefinger became more extended after blowback. The patterned bloodstain on the forefinger is away from the mouth - it could not have received this stain at this position. The left hand shielded the right at the bloody blowback (see text). Manipulation of the arms occurred post shotgun discharge/blowback .

The hands. The left wrist shows expirated blood (Fig. 12A) which is consistent with the victim being initially incapacitated by a severe blow to the back of his head. Blood was expirated through the nose and mouth and deposited on the left wrist while the victim was in a decorticate posture, with his hands near his mouth.

The palm and the dorsal distal fingers of the left hand are stained with a coating of blood (Figs. 12A and 12C). This is the result of the left hand being within centimeters of the mouth to intercept much of the blowback effluent following the intraoral shotgun blast. The left index finger, however, has a patterned bloodstain, where both the thumb and finger three shielded this finger (inset, Fig. 12A). These blood patterns and the soot (Fig. 8) on the left hand indicate the position and a close proximity of the left palm and fingers to the mouth at the time of bloody blowback.

The radial part of the proximal left palm (Fig. 12C), is a smear that starts at the base of the palm and goes toward the wrist. The size of the smear and its location indicate the transfer stain on the right hand is from the smeared area on the left hand's palm.

When the area of soot deposition on the left hand is included in the homicide scenario (Fig. 8), it indicates an assailant placed the victim's left hand over the barrel as shown in the simulation (Fig. 3B) before firing the shotgun. The stock of the shotgun was unsupported and when it was discharged, the recoil tore the muzzle out of the mouth. The left hand dropped to the grass while rotating 90 degrees counterclockwise so that the palm was juxtaposed to the mouth by the time of the bloody blowback. This supports the observation of a short delay from a contact or near contact gunshot into a skull to the bloody blowback event (Burnett, 1991).

The right hand was likely within centimeters of the mouth, behind the left hand (Figs. 1A and 1B), at the time of receipt of its blood spatter. Regardless of the source of the blood, either from expiration or the bloody blowback event, the right hand was shielded by the victim's left hand. This spatter could have occurred only in the homicide scenario, since in the suicide scenario the right hand would be at the trigger of the shotgun (Fig. 3A), a position where blood deposition such as seen on the right hand could not have occurred.

Post shotgun/blowback events. After blowback, passive bleeding from the mouth and nose continued for a short time creating the majority of the stain in the grass beneath and in front of the victim's head (Figs. 11A, 11C and 11D). The position of this stain in relation to the head indicates that bleeding from the mouth and nose was more substantial than from the left ear. In addition, part of the stain in the grass is from the blowback event itself (Figs. 11C and 11D). The accumulation of blood contacted the right shoulder of the bathrobe, where there was serum wicking (Fig. 15C).

The assailants, during the staging of the colonel's body, manipulated his arms and hands. There was a postmortem modification of the scene in regards to forefinger and thumb of the left hand and the position of the right hand (Fig. 16). During the adjusting the bathrobe and pajama bottom to the positions seen in Fig. 1, the upper part of the body was lifted bringing the right hand under and into the palm of the left hand. Blood was transferred from the left hand palm (arrow, Fig. 12C) to the right hand (Fig. 13C). The left and right hands came into contact with the face and left blood smearing/transfer (Fig. 14B). When the upper body was released, the right and left hands attained positions slightly different than their premanipulation positions.

Figure 17. Death scene photograph showing the colonel's bathrobe tucked between his legs at the crotch (arrow).

The body position, clothing and the shotgun

The body position. The blow to the back of the colonel's head is documented in the previous paper (Sabow and Burnett, 2011). The brainstem was severely injured by the blow. Such an injury has a high probability of causing decerebrate and decorticate posturing (Posner et al., 2007).

Lip and tongue biting, which occur with decerebrate and decorticate posturing (Posner et al., 2007), were documented for the colonel (Sabow and Burnett, 2011). The expirated bloodstains G and H in the grass (Figs. 2 and 10) occurred when the colonel was shifting between decerebrate and decorticate posturings. The expirated bloodstains were deposited at different positions in the grass (stains G and H) and the left ventral arm as the colonel transitioned between seizures. The body of the colonel (Fig. 1) was found in a decorticate posture, the position when death occurred.

The bathrobe. The initial perception by an inexperienced person of the colonel's bathrobe's position and configuration when the scene photographs are first examined is that it adheres to a suicide scenario. That is, the colonel was sitting in that patio chair, inserted the shotgun in his mouth, placed his left hand around the barrel at his mouth and with his right hand depressed the trigger (Fig. 3A). It is unusual he would tuck the bathrobe between his legs to his crotch (Fig. 17) prior to the shotgun discharge, but this feature did not initially contribute to the suspicion of body staging. However, several other scene images with the patio chair on top of the colonel revealed an extraordinary feature of the bathrobe: it was also tucked between the legs at the buttock (Fig. 18).

Figure 18. Scene photographs of the showing the bathrobe tucked between the colonel's posterior legs to his buttocks. A: Photograph of the colonel from the rear; the red dashed lined approximates the lower hem of the bathrobe under the chair seat. B: Enlargement of A (enhanced in Photoshop). The bathrobe folds into the buttocks. C: An anterior view of the colonel showing the configuration of the bathrobe under the patio chair. D: Enlarge from C; the bathrobe can be seen clinging to the buttock (enhanced in Photoshop. This documents the folding of the bathrobe into the buttocks and not a snagging by the chair of the bathrobe. E: A simulation using a mannequin that approximates the rear folding of the bathrobe into the buttock of the victim. No photographs of the body in the found position with the chair removed were available. The video of the scene processing showed none were taken.

The anterior of the body shows the tuck in the bathrobe from the knees to the crotch (Fig. 17, arrow). The posterior of the body (Fig. 18A), the bathrobe has the initial appearance of having been snagged by the patio chair when the victim fell backward as alleged to have occurred in the suicide scenario. However, enhancement of this image (Fig. 18B) reveals the folds in the bathrobe converge toward the proximal legs at the buttocks. Another image (Fig. 18C) shows the bathrobe tightly applied to the buttock and upper left leg through the webbing of the patio chair (Fig. 18D). A simulation of the bathrobe on a mannequin (Fig. 18E) shows in order to have the configuration of the folds as shown on the victim (Figs. 18A and 18B), the bathrobe must have been tucked between the legs at the buttocks.

It is impossible for the colonel to have tucked in his bathrobe both front and back prior to the alleged suicide in a patio chair. These features must have been performed by somebody else. The body was staged.

It is unfortunate pictures of the colonel at the scene were not taken with the patio chair removed. The video recording of the scene processing showed there were no photographs taken of the rear of the body from the removal of the chair to turning the body onto its back. If those pictures had been taken, the staging of the body would have been obvious. Perhaps if Nordby (2004 and 2006) had discovered this feature of the body, he would not have concluded the colonel died by suicide.

The shotgun. The discovery for this case had scant information concerning the shotgun except for the comment, “...the muzzle of the shotgun was visually examined which disclosed what appeared to be minute amounts of tissue blowback within the barrels” (NIS, 1991). No blood deposits or anything else connected to the colonel’s death was noted on the shotgun. In the suicide scenario, extensive bloodying of the shotgun should have occurred. The lack of any blood on the shotgun and the lack of fingerprints on the exterior surface of the shotgun (Nis, 1991) indicate the shotgun was cleaned prior to being placed under the colonel’s legs.

Reconstruction of the Homicide

The colonel was subdued by three persons. The attackers planned to stage a suicide. In order for this plan to work, they had to be certain that their victim did not show signs of their attack (bruises, abrasions, grass stains on the clothing, etc.). While the victim was being held, likely by a person holding each arm, his head was forced down and a cricket bat or a similarly constructedclub was brought down with considerable force on the right occiput of the colonel's skull (Fig. 19A). The person who administered the blow took care to be sure the edge of the club (the outline of the club can be seen in Fig 19B and shown by dashed line in Fig. 19C) was not in a position to abrade the scalp. A depressed cranial fracture on the right occipital skull (Sabow and Burnett, 2011) is evident. The victim fell to the ground and lay on his right side, severely wounded but still alive. He continued to breath for at least several minutes and aspirated over one-half liter of blood into his right lung (Singhania, 1991). While in this unconscious state, he exhibited brainstem convulsions (decerebrate and decorticate posturing, see Posner et al., 2007) during which time he lacerated and bruised his upper and lower lips as well as his anterior tongue (Sabow and Burnett, 2011). In this condition and near death, the victim had "central neurogenic hyperventilation" which characteristically occurs with severe brainstem trauma (Posner et al., 2007) and during which he expirated blood (also see Feldman, 1994) onto his left wrist (Fig. 12B) and onto the grass (bloodstains G and H, Figs. 2 and 10). Because he continued to live during this period, there was sufficient time elapse for a hematoma to form over the depressed skull fracture (Sabow and Burnett, 2011) as well as swelling (Sabow and Burnett, 2011; Remley, 1996). From the time of the initial attack until the time he expired, bleeding was occurring from the lacerated lips, the lacerated tongue and the posterior pharynx. This blood was both expirated and inhaled. The shearing force to the brainstem that would have followed a blow to the back of the skull resulting in such a depressed skull fracture, also would have extensively and irreversibly injured the brainstem (Posner et al., 2007). In all likelihood the blow caused hemorrhage within the substance of the brainstem, in addition to having caused laceration of the blood vessels supplying the brainstem.

Figure 19. A: Simulation of the club blow to the back of the Colonel's head. The "club" in this depiction is a field hockey stick. It is more likely that the weapon utilized was a cricket bat (or similar-shaped club) where the flat part and end of the bat is similar to the hockey stick depicted here. In order to avoid abrasions during the hit, it is necessary to have the club wide enough so that an edge does not catch and abrade the scalp and the club needs to be flat or with a slight curvature so that there is no focusing of the kinetic energy in the impact that will cause abrasion. A baseball bat could not have been used to create this wound. B: The posterior of the victim's head showing the patterned massive swelling, as outlined by bruising caused by the club blow. C: Same as B, but a dashed line indicates the likely shape of the end of the club.

The blowback blood that stained the victim's left hand and the grass exited from the entrance wound, the mouth. It has been shown that the mouth was directly in front of the palms of both hands, with the left hand shielding the right (Fig. 16). The left forearm intercepted expirated blood from the nose and the left palm intercepted blowback blood (Fig. 12). The bathrobe and pajama were at 90 degreesfrom the trajectory of blowback and thus both were devoid of direct blowback effluent, although the bathrobe as well as the face received some reflected blowback blood (Figs. 14 and 15) from the left palm and fingers.

The shotgun was discharged into the colonel’s mouth without bracing. This resulted in the rapid muzzle withdraw in recoil from the colonel’s mouth. The left hand received soot through the sides of the mouth while the barrel of the shotgun was still in the victim’s mouth. Some organic debris was deposited in the barrels of the shotgun (NIS, 1991). There was a two-phase blowback. The initial blowback involved primarily soot and GSR which deposited on the medial aspect of the forefinger and lateral aspect of the thumb (Fig. 8). After the rapid removal of the shotgun muzzle from the colonel’s mouth, the unsupported left hand rotated counterclockwise 90 degrees while dropping to the grass to a position in front of the mouth and the colonel's head rotated back to its original position where the second phase blowback, the bloody blowback, occurred. The bloody blowback hit the left palm, dorsal distal fingers (Fig. 12A) and the grass in front of the left hand (Fig. 11E).

The GSR evidence shows that the shotgun leaks GSR from the trigger housing and breech. There were no GSR focal concentrations that would occur with the breech in close proximity to the bathrobe or pajama bottom in the suicide scenario. Indeed, the bathrobe did not have significant GSR association, except possibly on its lower hem (Nordby, 2006), despite being the article of clothing that would be exposed to GSR contamination (Fig. 1) regardless of the death scenario. The shotgun breech was away from the bathrobe and pajama bottom as the homicide scenario (Fig. 3B) would predict. In addition, the pajama bottom of the victim, although mostly covered by the bathrobe when the body was found, had significant levels of GSR associated in areas that were under the bathrobe cover. The pajama buttocks were GSR contaminated which could be due to either the GSR-laden cloud from the shotgun’s breech leakage drifting over the lower half of the victim or the shooter, who was contaminated with GSR, participated in staging of the body. It is apparent the bathrobe was partially folded over itself and hiked up on the body when the shotgun discharged. The front upper chest of the bathrobe was exposed at the time of the shotgun blast because some blood spatter was observed in this area (Figs. 15A and 15B). The bathrobe of the upper chest was not contaminated with GSR. This suggests during initial soot- laden blowback that the left hand did not deflect GSR to the chest, unlike the blood-laden blowback which hit the left palm and dorsal distal fingers and deflected some blood back onto the bathrobe and face.

The behavior of the shotgun would be quite different in the suicide scenario in that it would be stationary with the stock on the ground upon discharge into the mouth. The kinetic energy of the blast would jerk the head back from the muzzle due to there being no exit wound. At the time of the head jerking back, blowback would occur and contaminate the bathrobe and shotgun with GSR, BSR, blood, bone and other tissue. The left hand would immediately begin its drop from the shotgun barrel and would be in a position to receive little, if any blood or if it did, the blocking effect of the shotgun barrel would be apparent in the bloodstains on the left hand. In addition, there was no mention in any of the discovery that the shotgun had bloodstains on its surfaces. Within seconds after the shotgun blast in the suicide scenario, the colonel would fall backward and to his right from the chair. The final position of the body (Fig. 2) in relationship to the location of the patio chair that the colonel allegedly sat for the suicide (Fig. 3A) also makes the suicide scenario completely untenable. Brainstem destruction, as had to have occurred, causes all muscles to immediately become flaccid (Posner et al., 2007) and would not allow for the victim essentially "jumping" into a fully stretched-out position.

After the intraoral shotgun blast, postmortem manipulation of the colonel's bathrobe took place. The assailants cleaned the exterior of the shotgun and placed it under the decedent’s legs in order to appear that he shot himself while sitting in a patio chair, falling backward and to his right and on top of the shotgun. The lawn chair was placed on top of the body to complete the suicide image. The assailants, in an apparent assassin faux pas, tucked the bathrobe between the legs both front and rear. The rear tuck could have been done to support the appearance of entanglement of the bathrobe by the patio chair (Fig. 18A) which "pulled" the chair to its position on the body when found. The setup of the homicide and body staging show there was a sophisticated, but ill- conceived plan for the homicide and postmortem manipulation of the body with the intent to hide the circumstances of the colonel’s death.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Dr. Jozef Lebiedzik for his extraordinarily valuable assistance in this project.

References

Anonymous. 1991. Physical evidence report, (V) SABOW, James Emery. California Department of Justice., Riverside Regional Criminalistics Laboratory.

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT-DOJGSRREPORT.pdf.

Burnett, B.R. 1991. Detection of bone and bone-plus-bullet particles in backspatter from close- range shots to heads. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 36(6):1745-1752.

Burnett, B.R. 2005A. The gunshot residue evidence of People v. Robert Blake: A case of forensic alchemy.

meixatech.com/BLAKE.pdf.

Burnett, B.R. 2005B. Investigation of the death of Colonel Sabow: Gunshot residue, back spatter and death scene analysis. Report to Congressman Duncan Hunter, Chairman of the Armed Services Committee, Congress of the United States.

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT- BURNETT.pdf.

Burnett, B.R. 2007. People v. Phil Spector. The missing gunshot residue evidence and misinterpreted blood spatter evidence. The Daily Transcript (San Diego). Wednesday, August 22, 2007

Burnett, B.R. and Sabow, J.D. 2007. Investigation of the death of Colonel James Sabow, USMC. Update: March 8, 2007.

meixatech.com/COLSABOWHOMICIDE.pdf

Chavez, C., Crowe, C. and Franco, L. 2001. The retention of gunshot residue on clothing after laundering. International Assoc. for MicroAnalysis. 2(1):1-7.

Cao, X., L.Q., L.Q. Ma, S.P. Singh, M.Chen, G.W.Harris, and P. Kizza. 2003. Field demonstration of metal immobilization contaminated soils using phosphate amendments. Final Report, Florida Institute of Phosphate Research. FIPR Project 97-01-148R.

DiMaio, V.J. 1999. Gunshot wounds - Practical aspects of firearms, ballistics and forensic techniques. Second edition. CRC Press., New York. 402 pp.

Dodd, M.J. 2006. Terminal ballistics - A text and atlas of gunshot wounds. Taylor and Francis, New York. 212 pp.

Fackler, M.L. 1994. Comments regarding the death of Colonel James E. Sabow.

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT-FACKLER.pdf.

Feldman, J.L. 1994. Comments concerning the death of Col. James Sabow.

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT-FELDMAN.pdf.

Gibbs, S. 1991. MCAS El Torro EMS Report. (Emergency Medical Service).

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT-GIBBS.pdf

Gilman, S. and Newman, W.S. 2003. Essentials of Clinical Neuroanatomy and Neurophysiology,10th Edition, Sid and Newman, F.A. Davis Co.

James, S., P.E.Kish, T.P. Sutton. 2005. Principles of bloodstain pattern analysis. Theory and practice. Taylor and Francis. New York. 542 pp.

Maritz, P. 2006. Death Investigation, SD Forensic Lab #05-346, James Emery Sabow, victim. State of South Dakota, DCI Forensic Laboratory, Office of the Attorney General.

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT-MARITZ.pdf

Martinez, M.V. 2000. P-GSR detection on clothing and in automobiles. International Assoc. for MicroAnalysis. 1(2):2-3.

Mann, M. and Espinoza, O. 1993. The incidence of transient gunshot primer residue in Oregon and Washington bow hunters. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 38(1):23-27.

Niemeyer, W.D. 2000. Gunshot residue from strange places. International Assoc. for MicroAnalysis. 1(3):8-9.

NIS. 1991. Naval Investigative Service: V/Sabow, James Emery/Col USMC (Deceased). Examination of victim at death scene and at Coroner’s facility. 6 pp., page 5 or 6 missing.

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT-NIS.pdf

Nordby, J. 2004. Shotgun death of Col. Sabow. Report under Federal Contract HQ00095-04-C- 002. Law Enforcement Policy and Support (Department of Defense).

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT-NORDBY.pdf

Nordby, J. 2006. Shotgun death of Col. James E. Sabow. Report under Federal Contract HQ00034-05-R-1014. Law Enforcement Policy and Support (Department of Defense).

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT-NORDBY2.pdf

Posner, J.B., Saper, C.B., Schiff, N. and Plum, F. 2007. Plum and Posner's diagnosis of stupor and coma. New York: Oxford University Preee.

Remley, K.B. 1996. Neurosurgery-Neurradiology Combined Conference concerning James Sabow, University of Minnesota, Medical School, Department of Radiology, Neuroradiology Section.

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT-REMLEY.pdf

Romolo, F.S. and P. Margot 2001. Identification of gunshot residue: a critical review. Forensic Science International. 119:195-211.

Rubinstein, D. 1996. Evaluation of the James Sabow death.

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT-RUBINSTEIN.pdf.

Sabow, J.D. 2005A. Summary of 15 years of a controversial case: The death of Colonel James Sabow.

www.meixatech.com/SABOWSUMMARY.pdf.

Sabow, J.D. 2005B. Colonel James Sabow, USMC. Analysis of Jon Nordby’s report of the death investigation. Prepared for Chairman Duncan Hunter and the Senate and House Armed Services Committees. www.meixatech.com/EVALNORDBYREPORT-SABOW.pdf.

Sabow, S. 1991. Naval Investigative Service: summary of the interview of Sally Sabow.

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT-SSABOW.pdf.

Sabow, J.D. and Burnett, B.R. 2011. The distinction between instantaneous and sudden death and how it is critical in equivocal death investigations. Investigative Sciences Journal (preceding article in this journal issue).

Sandring, S. et al. 2005. Gray's Anatomy. Elsevier, Ltd. 1627 pp.

Schwoeble, A.J., L.G. Harrison, E. Foster, and D.M. Freebling. 2006. SEM analysis of gunshot residue samples. DCI Forensic Laboratory, Cse Number 05-346. Sabow, James Emery. Report, RJLee Group, Inc.

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORT-RJLEE.pdf.

Singhania, A. 1991. Autopsy record: Sabow, James Emery. Case Number 91-00474-SU. Orange County Sheriff-Coroner, Forensic Science Center. Report: 6 pages.

www.meixatech.com/SABOWREPORTAUTOPSY.pdf.

Weather Underground. 1991. History for Santa Ana, CA.

www.wunderground.com/history/airport/KSNA/1991/1?22/DailyHistory.html.

White, R.S. and M.L.Gross. 1994. Deposition of gunshot residue at various distances from discharging firearms. The Seminar. 4:8-14.

Wyngaarden, J. and L .Smith. 1985, Cecil Textbook of Medicine, W.B. Saunders Company.

Zeichner, A., H.A. Foner, M. Dvorachek, P. Bergman, and N. Levin 1989. Concentration techniques for the detection of gunshot residue by scanning electron microscopy/energy dispersive X-ray analysis. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 34(2):312-320.

________

This article appeared

at The Tico Times

The undoing of Gary Webb and today's news organizations

John McPhaul

October 29, 2014

Screengrab from interview by School of Authentic Journalism in Merida, Mexico, 2002.

See also: Reviving the messenger: Gary Webb's tale on film

I haven't seen "Kill the Messenger," the movie about the rise and fall of the crusading San José Mercury News reporter Gary Webb, but I did know Gary Webb.